Treatment for drug-resistant malaria possible within 10 years: MIT-SMART-NTU team

A drug that could potentially treat severe or drug-resistant malaria by boosting one’s immune system is expected to hit markets within the next decade, said the scientists behind its discovery on Monday (8 October).

Moreover, the research could lead to other drugs against cancer and infectious diseases such as dengue and tuberculosis.

Consequently, it may “hold the key to addressing multi-drug resistant diseases”, said Dr Ye Weijian, the study’s lead author, a Nanyang Technological University (NTU) graduate under the Singapore-MIT Alliance for Research and Technology (SMART) Graduate Fellowship.

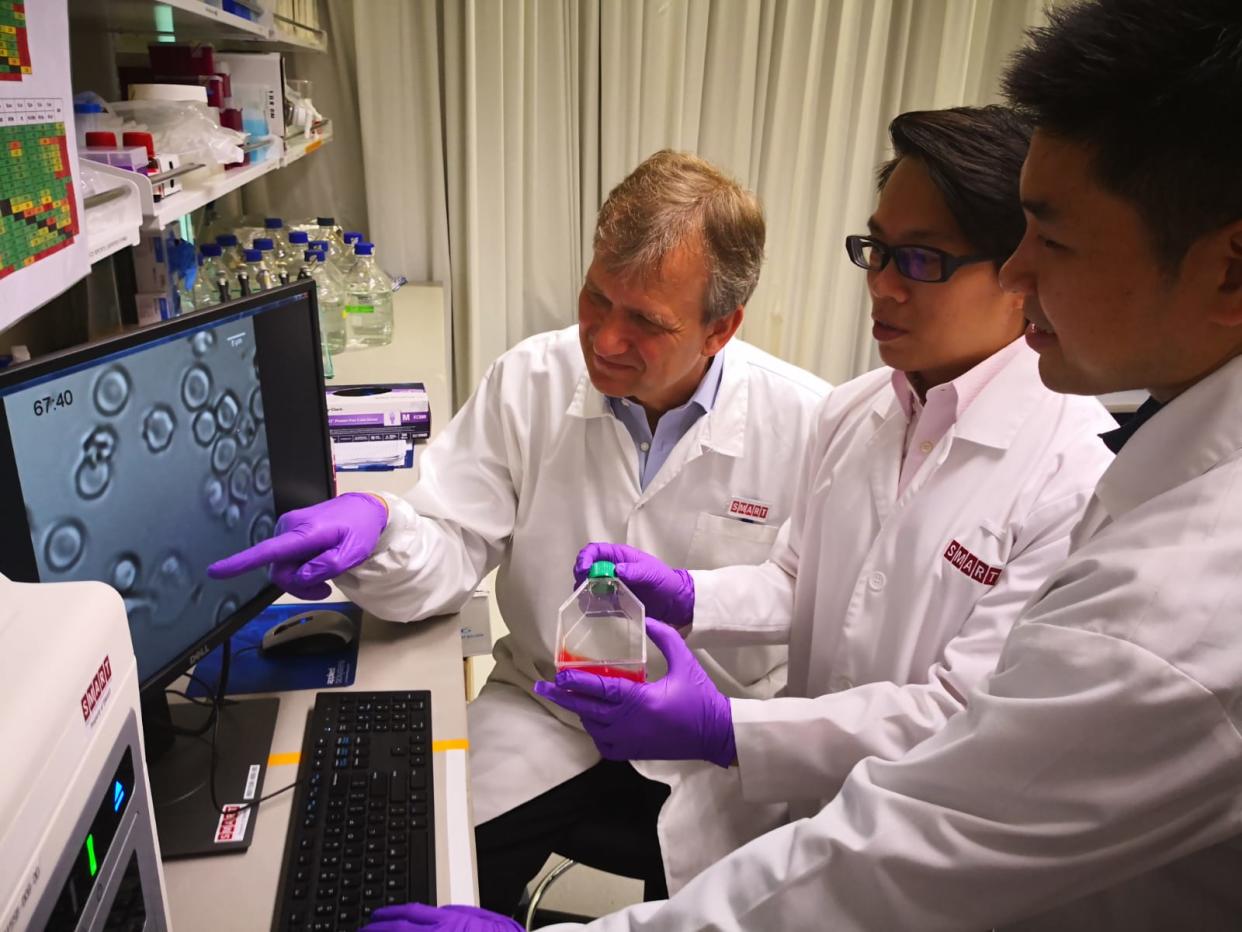

The joint research team of 14 local and international scientists – including Ye – from Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), SMART and NTU had established that Natural Killer (NK) cells with higher levels of MDA5, a pathogen recognition receptor, respond better to malaria infection.

NK cells are the first-line-of-defence cells that destroy infected red blood cells upon detection. MDA5, located inside NK cells, helps to identify bacteria and viruses, which triggers the cells into attacking and killing infected red blood cells.

However, some people have more responsive NK cells than others due to human genetic variation, said the team. For their study, they extracted cells from 25 patients from a hospital in Bangladesh.

Experiments conducted by the team during the four-year study showed that responsive NK cells with MDA5 intact could reduce the malaria parasite by over 60 per cent, while those with MDA5 removed could only reduce the parasite by 20 per cent.

By using a synthetic drug compound in their lab tests, the team was able to improve non-responsive NK cells by activating MDA5 artificially. Depending on the concentration of the drug compound, this can more than double the chances of reducing the malaria parasite to above 50 per cent for infected patients with non-responsive NK cells.

The drug, however, does not “further improve” the chances of reducing the malaria parasite for individuals who already have responsive NK cells with MDA5 activated.

Professor Chen Jianzhu, professor of biology at MIT and SMART lead investigator of the Infectious Diseases Interdisciplinary Research Group, said, “With no viable vaccine for malaria in sight, coupled with increasing loss of efficacy in anti-malarial drugs and prophylaxis as anti-malarial drug resistance, this breakthrough discovery will open up new avenues for targeted approaches in our fight against malaria.”

For one, Professor Peter Preiser, chair of NTU’s School of Biological Sciences, who is part of the team, stressed that the drug aims to “help the host fight the parasite more effectively”, rather than to “increase the likelihood of anti-malarial drug resistance”.

Currently, the team’s priority would be to formulate a drug that is suitable for human administration, said Prof Preiser. Also in the pipeline for the team is a study into the effectiveness of MDA5 on dengue-infected red blood cells.

Prof Preiser said “optimistically”, the team is forecasting at least five years between discovery and the actual malaria drug on the market but the “normal” time frame would be 10 years.

Malaria, a mosquito-borne parasite, affected 216 million people worldwide in 2016, of whom 445,000 died, according to statistics by the World Health Organization (WHO).

About six per cent of these fatalities occurred in South-east Asia.

While Singapore has maintained its malaria-free status – achieved by having zero locally transmitted cases for at least three consecutive years – granted by WHO since 1982, the Republic saw 24 reported cases this year as of last Thursday, according to the Ministry of Health’s (MOH) weekly infectious disease bulletin. The median number of reported cases in Singapore for 2013 to 2017 was 40.

Amid a growing “super malaria” situation in South-east Asia in 2017, the MOH announced last September that there were no such cases reported in Singapore. “Super malaria” refers to a strain that is resistant to current anti-malaria drugs.

However, the risk of the disease remains present in Singapore, stressed Preiser.

“Singapore is a big travel hub, people come over from all over, from malaria-endemic regions. They come in here, they could transmit it and they, in turn, could get ill from it as well,” he added.

Findings of the team’s research, funded by the National Research Foundation Singapore through SMART at the Campus for Research Excellence and Technological Enterprise, were published in a peer-reviewed academic journal PLOS Pathogens last week.

Other Singapore stories:

Man who molested girl he met at Jurong playground jailed, caned

Employers not allowed to hold on to maids’ money from next year: MOM