What University Presidents Can Learn From Past Protests

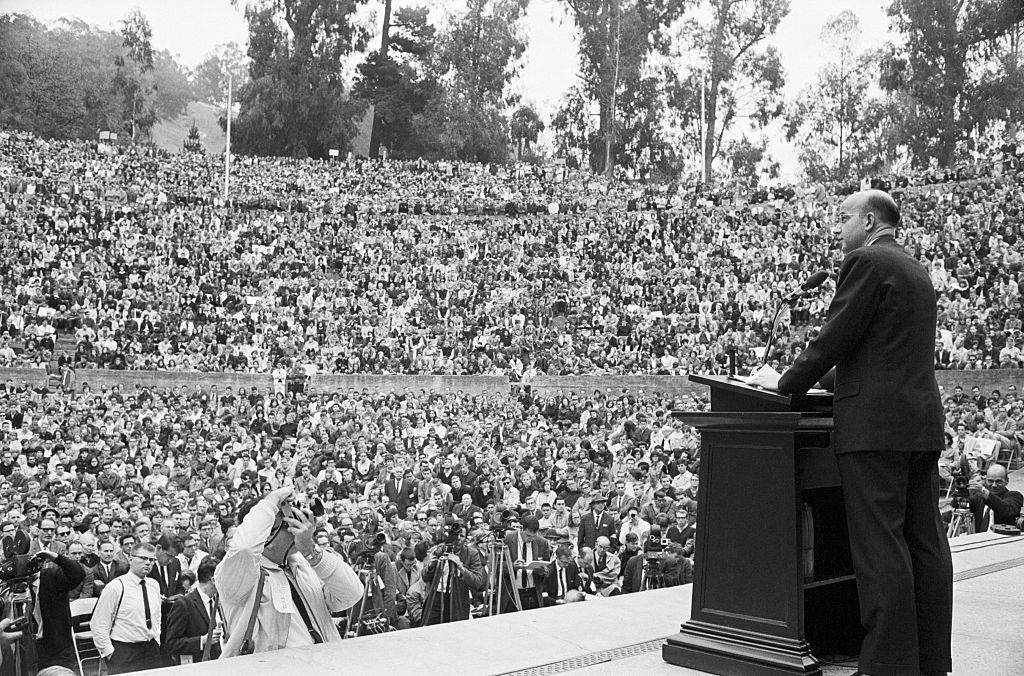

University of California President Clark Kerr addresses 13,000 persons in the Greek Theater during a convocation called to seek the end of the demonstrations on the UC campus in 1964. Credit - Bettmann Archive/Getty Images

This year, around 2,000 students were arrested on college campuses at the behest of their own institutions’ leaders. And it was not one or two leaders. Presidents and chancellors approved arrests of student protesters at UCLA, Columbia University, Indiana University Bloomington, University of Texas at Austin, Pomona College, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Emory University, City University of New York, Yale University, and Washington University in St. Louis, among dozens of other campuses. At the University of Southern California, there were two police sweeps to remove students' Gaza solidarity encampments from campus. Arrests during some commencement ceremonies occurred at institutions whose leaders did not cancel graduation exercises altogether.

Campuses may be quieting as summer sessions have arrived. But these recent actions should concern all Americans. Many of the institutions that lead knowledge production are led by college presidents who, in what was at best a misguided attempt to address what they framed as concerns about campus safety, suppressed dissent. How can we trust these universities to solve politically hostile problems like climate change? Why believe that the education on those campuses will teach students how to consider different viewpoints? What are we teaching this generation of students?

In contrast, we might look at another period of student unrest: the 1960s. During that tumultuous era, student protesters were frequently confronted by police and the National Guard; many faced arrest and violence, with some even shot or killed. Images from the arrests at Columbia University in 1968 and of the National Guard and local and state police shootings at Kent State and Jackson State in 1970 have recirculated in recent weeks, amid this year’s campus protest crackdowns.

But some presidents of that era actually engaged with students, even if begrudgingly, in extended dialogue to end demonstrations, and challenged politicians’ negative characterizations of student protests. Their approach was essential to academic freedom, stifling political interference, and modeling democracy.

On Feb. 1, 1960, four freshmen at North Carolina A&T, a public Black College in Greensboro, held a sit-in at the local F. W. Woolworth’s whites-only lunch counter. The Black students were denied service because of their race, and the demonstration sparked hundreds of other college students across the South to launch sit-ins at segregated lunch counters. In March 1960, UCLA students joined those efforts and launched the Los Angeles-area pickets at Woolworth stores in solidarity with Black students in the South. UCLA and Santa Monica City College students picketed the Santa Monica Woolworth. Los Angeles State College students demonstrated at the downtown L.A. store. Led by Jesse Morris, a UCLA senior and chair of the Southern California Boycott committee, California students called for “help in our fight for universal equality.”

Two months later, in May 1960, California students captured the nation’s attention for disrupting a U.S. House of Representatives Un-American Activities Committee meeting in downtown San Francisco.

At the state level, those activities motivated the California State Senate Un-American Activities Subcommittee to investigate student activity on the state’s college campuses. They were also responding to a shift in University of California policy. Whereas the university had previously denied recognition to student groups dedicated to specific causes, in fall 1960, UCLA’s new chancellor Franklin D. Murphy granted the campus NAACP chapter recognition as an official student group.

More From TIME

The subcommittee released a report regarding “radical student groups” in June 1961. It concluded that communist behavior would “plague California campuses in the near future.” Politicians often conflated students’ civil rights activism and other activities with communism, which they treated as threatening to the United States.

UC President Clark Kerr prepared a reply shortly afterward. Kerr noted that the subcommittee report “found no specific evidence of successful infiltration by subversive groups of our faculties or of our representative student organizations.”

But he did not just defend the students from that charge. He framed his reply in terms of the principles that guided university leadership, including that: “Freedom to speak and to hear is maintained for students and faculty members.”

“These policies in their totality assure freedom without license,” Kerr concluded. “We cannot and will not neglect any one of them.” While Kerr challenged politicians’ framing of students’ and professors’ off-campus activities, other administrators engaged students during on-campus protests.

Read More: Academic Freedom Is More Important Now Than Ever

Another example of a successful approach came at the University of Chicago in 1962, when student and community activists held a rally outside of the administration building, protesting how the university’s real estate investment practices perpetuated housing discrimination on Chicago’s South Side. Chicago’s rapid acquisition of land near campus meant property managers continued to discriminate, even after the university became the landlord.

Soon, student demonstrators entered the building and occupied University of Chicago President George Beadle’s office. The students demanded the university immediately end discriminatory rental practices in university-owned properties.

Beadle was not a fan of the students’ demands. He felt the sit-in in his office was “emotional.” Plus, he added, the university “cannot ‘negotiate’ with any group of students.” But Beadle did not immediately call police on the students who occupied his office. Instead, over a two-week period, he and other university leaders regularly met with students to discuss demands.

The back-and-forth was contentious. University leaders felt it would be a burden to disrupt long-standing rental practices in the neighborhood. Some administrators felt white residents would leave if Black people were allowed to move into majority- or all-white buildings. But the students were diligent. Student pressure and negative media coverage of the protests led Beadle to form a faculty commission to evaluate university property and discrimination. The students suspended their occupation of the building as a result. One of the Chicago demonstrators went on to become U.S. Senator Bernie Sanders.

Two months later, Chicago trustees changed university policy: “All housing properties of the university, whether operated as commercial properties, or specially for housing of students and faculty, are available for university students or faculty members regardless of race or creed.”

The students considered the change in policy a victory, especially considering that the university had previously dedicated resources to protecting racially-restrictive housing covenants during the 1930s and 1940s, according to historian Arnold Hirsch.

Neither Beadle nor Kerr were perfect leaders, but their approach in these instances is instructive regarding the perils of outside pressure on how to handle campus unrest. Later in December 1964, hundreds of students occupied Sproul Hall on Berkeley’s campus as part of the Free Speech Movement. As a result, Edwin Meese, deputy district attorney of Alameda County, called Governor Edmund “Pat” Brown to inform the governor that demonstrations were out of control. Kerr, Brown, and UC Board of Regent chair and businessman Edward W. Carter agreed by telephone to have police intervene. Similarly, at the infamous shooting at Kent State in May 1970, Ohio National Guardsmen were on campus at the directive of Ohio Governor James Rhodes, not Kent State President Robert I. White.

Read More: The Dangers of Curtailing Free Speech on Campus

But the successes that came when presidents protected student protesters from outside meddling are worth remembering as students return to campus next fall. We have seen all too often what happens when elected officials and institutional leaders move away from tolerance and dialogue. If anything, the harsh crackdowns on this year’s protests have brought disruption and distrust. Instead of calling in police and security forces to suppress protest, university leaders owe it to students to engage with them.

A president should never pass on a teaching moment. A recent Washington Post report noted that divesting endowment funds from entities doing business in Israel is likely more complex than South African divestment during apartheid. Students don’t know the intricate details of endowment portfolios—but why not teach them? Show students how divestment works, and do not leave a campus town hall early when students disagree, like they did at Rutgers University. Unfortunately, too many have forfeited their role as educator for that of an administrator.

There were leaders at Brown University, Northwestern University, and other campuses who agreed with students to add divestment to future board meeting agendas for consideration. Michael S. Roth, president of Wesleyan University, publicly explained why he did not call police on students. These approaches should be the norm.

Preparing students for engagement in a democratic society is a critical task for institutions of higher education. Past student activists were critiqued then but are often celebrated today for their democratic clarity as youth—with the Free Speech Movement Café on Berkeley’s campus as an example. Today’s students have faced similar critiques. But there is hope. Recent campus demonstrations show that future generations also care to have challenging conversations about war, human rights, the perils of capitalism, and democracy. Today’s cohort of academic leaders should better demonstrate that they’re up to the challenge.

Eddie R. Cole, Ph.D., is Professor of Education and History at UCLA and a Harvard Radcliffe Fellow. He is also the author of The Campus Color Line: College Presidents and the Struggle for Black Freedom (Princeton University Press).

Made by History takes readers beyond the headlines with articles written and edited by professional historians. Learn more about Made by History at TIME here. Opinions expressed do not necessarily reflect the views of TIME editors.

Write to Made by History at madebyhistory@time.com.