The unsung melodies of Kurt Cobain

It's been twenty-five years since Nirvana released their second album Nevermind, a record that introduced grunge to the mainstream and changed rock and roll forever. EW has been chronicling the band throughout their career, and in a 2014 issue of the magazine, we spoke to frontman Kurt Cobain's closest collaborators — including his bandmates Krist Novoselic and Dave Grohl — to ask the question: what would his music sound like today? Revisit the story below.

###

Kurt Cobain's old home sits in Seattle's quiet Denny-Blaine neighborhood, a posh place with water views where people probably kept to themselves even before an iconic rock star died in their midst. The room over the garage where the Nirvana singer's body was found on April 8, 1994, after he ended his life at 27 with a gunshot wound to the head, is now gone—and the house is isolated by a large fence, an imposing gate, and some Middle-earth-level greenery growing up around it, so fans tend to stick to Viretta Park next door. There, a pair of benches have acted as a standing tribute to Cobain, with decades' worth of messages etched into the wood by grunge pilgrims from around the world. I've made this trek myself multiple times, and as I sit on one of the benches, the same question that has occupied alt-rock devotees for the past 20 years tugs at me: Had he not died so young, what would Kurt Cobain's music sound like now?

In many ways, his death marked the passing of one of the last monoculture stars—a name you knew no matter what kind of music you were into. His band's three proper studio albums—1989's Bleach, 1991's Nevermind, and 1993's In Utero—are considered seminal, and all have gotten deluxe reissues as they've aged into classic-rock territory. But unlike Tupac, or Jimi Hendrix before him, Cobain didn't leave behind a trove of unreleased material for us to obsess over. There's the single "You Know You're Right," cut during Nirvana's last-ever recording session in January 1994; there are a handful of jams and song sketches released on 2004's With the Lights Out box set; and there's MTV Unplugged in New York, a recording that essentially served as Cobain's musical epitaph, and may have left the bread crumbs on the trail to where he could have been headed musically.

Filmed on Nov. 18, 1993, at a studio in Manhattan, the band's Unplugged session was unusual for being recorded entirely live to tape; most guests relied on multiple takes. Remembers former Nirvana publicist Jim Merlis: "The press [at the shoot] had been at the Stone Temple Pilots' Unplugged, and I believe they did every song, like, three or four times, and it was really boring. I was worried it could really, really go wrong."

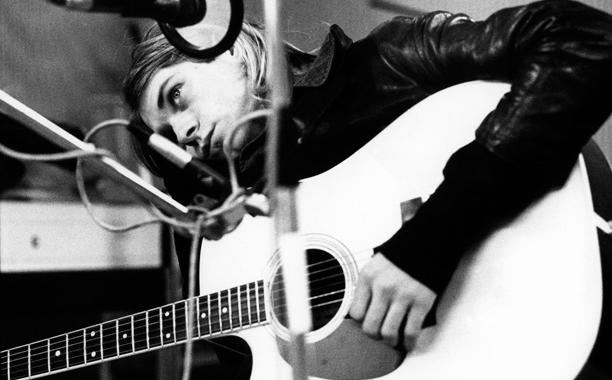

Image Credit: Frank Micelotta/Getty Images

It was also a strange set list, featuring very few established hits ("Come as You Are" would have been the only recognizable tune for radio listeners) and half a dozen covers, including a trio of songs by cult Arizona rockers the Meat Puppets, who also sat in. "[Nirvana bassist] Krist [Novoselic] told me they used to listen to early Meat Puppets stuff a lot when they were first starting out," recalls Meat Puppets frontman Curt Kirkwood. "We went out on tour with them in the fall of '93, and he asked if we'd do Unplugged. Kurt already knew which songs he wanted to do when he asked."

It's possible, of course, that even if Cobain had lived, Nirvana still would not have been long for this world. But Unplugged may have signaled the jumping-off point for wherever his musical muse was leading him. "My main feeling with the Unplugged thing was 'Wow, what do you do now? The passion was at such a high level,' " says Kirkwood. "I was in awe of the whole thing, because there wasn't much pretense and there was no glam. There was a lot of hoopla around them, but not from them. I think it would have been awesome to have a record or two of that kind of material. It's definitely some of my favorite stuff that they did." It was Cobain's apparently, too: "I remember Kurt calling his mother after the show and being like a little boy about how well it went," recalls Merlis. "He was so happy."

When Cobain died, R.E.M. frontman Michael Stipe told Newsweek: "I know what the next Nirvana recording was going to sound like. It was going to be very quiet and acoustic, with lots of stringed instruments. It was going to be an amazing f---ing record.... He and I were going to record a trial run of the album, a demo tape. It was all set up." The two were close friends (Stipe is the godfather of his only child, Frances Bean, and was one of three people—along with Cobain's wife, Courtney Love, and Sub Pop cofounder Bruce Pavitt—to speak at his private memorial), and Cobain had become obsessed with R.E.M.'s 1992 album, Automatic for the People. "He was talking about that record constantly. Loved it. He loved R.E.M. in general, and I think that's where he wanted to go," says Merlis. Eerily, Automatic was reportedly on Cobain's stereo when his body was found.

"The input of what went into that petri dish of his musical creativity was only a few things, and they were sort of random," Charles R. Cross tells me when I meet up with him in Seattle. Cross is the author of the definitive Cobain biography, Heavier Than Heaven, and the just-released Here We Are Now: The Lasting Impact of Kurt Cobain; as the editor of the dearly departed local music rag The Rocket, he was one of the few journalists in Cobain's orbit for the entirety of his musical life. Cross says Cobain wasn't a voracious record hound, but he was loyal to the things he liked, and each one affected him in some way. "The Vaselines, the Pixies," Cross says. "Let's say Kurt had 10 major influences, but he got something from every one of those influences." Throughout his life, there are markers of his obsessions, from his essay about tracking down an album by female post-punk band the Raincoats in the liner notes of early pressings of the 1992 comp album Incesticide to his endorsement of cult songwriter Daniel Johnston.

Cobain also had a passion for melody, and even beneath the alienating Steve Albini-provided scuzz that colors In Utero, there are some real hooks. Many of those were extracted by Automatic for the People producer Scott Litt, who was brought in toward the end of the sessions to sweeten up several tracks, including the lead single "Heart-Shaped Box."

"He loved pop music more than most of us did," says Charles Peterson, who was Sub Pop's in-house photographer and took many of the most iconic pictures of Cobain. "He sort of curated that last day of [England's] Reading Festival in '92, and when you look at that, there was L7 and Screaming Trees and Mudhoney, but also the ABBA cover band Björn Again. He was really into that ABBA cover band. It was genuine. I remember standing on the side of the stage and he looked up at me with this huge smile and was like, 'What do you think?' "

Despite his appreciation for "Dancing Queen," Cobain largely genuflected before revered oddballs like William Burroughs, whom he collaborated with in 1992. "Kurt would have had the luxury of working with anybody in the world, and in my opinion he would have chosen to work with outsider artists," says Bruce Pavitt over breakfast near his home in Seattle's Madrona neighborhood, just a stone's throw from Cobain's house. Last year, Pavitt released the book Experiencing Nirvana: Grunge in Europe, 1989, a memoir of the group's first international tour; he witnessed Cobain's development as a songwriter, and the two had countless conversations about music. When rumors started that Nirvana were considering jumping from Sub Pop to a major label in 1990, Pavitt recalls bringing him a gift of "the two least commercial records I had ever heard in my life": Daniel Johnston's Hi, How Are You and the Shaggs' Philosophy of the World. "Kurt might have worked with Daniel Johnston," Pavitt says. "He would have used his fame to shed light on artists on the periphery of culture. He did it with the Meat Puppets, too. That was his style. I can't see him jamming with Paul McCartney."

Of course, the surviving members of Nirvana famously did end up jamming with McCartney in 2012. It's a little hard to imagine Cobain participating in that kind of splashy pair-up had he lived, but the melodic line connecting him to the Beatles was undoubtedly there. "I was not that impressed with Bleach," Nevermind producer Butch Vig told me several years ago. "The only song to me that really stuck out was 'About a Girl.' That had a very Lennon-McCartney melodic structure. That, I think, was an early template of where Kurt was going." Cobain might actually have looked to the world's most famous band in other ways. "Even if Nirvana had stayed together, they could have pulled a Beatles and just decided not to tour, or really restrict it," says Pavitt. "By '94, Kurt was kind of over being an international rock star."

Cross agrees: "My vision is Kurt as a dean, a statesman, but he's still writing and putting out really weird records that Jack White is putting out on vinyl editions," he posits. "It's something very off-kilter like that. Even toward the end of his career, he was tired of screaming and tired of big arenas, and he wanted to have more control. He's Neil Young, minus the fancy autos and train sets."

Image Credit: Paul Bergen/Redferns

The last Nirvana song ever recorded was "You Know You're Right," and it's as prototypical as the band got: A quiet, throbbing intro leads into slowly escalating guitars and a massive explosion in the chorus, all driven by Cobain's weathered yawp—an instrument that had the potential for much more than stadium screaming. "Kurt had a really special voice with a lot of character," Grohl told me during a conversation about the making of Nevermind. "You can see a lot of it on Unplugged, where his voice will break. He'll go from having a smooth, pretty voice, and then he'll pull it into his throat and make it break up." Cobain was known for being a tinkerer, too. "I remember Kurt played In Utero for me on a boom box in his kitchen while I was taking photos of the collage for the back of the album," says Peterson. "I thought it was pretty huge, but he was really worried. He kept asking if I liked it. I don't think he was ever happy with the mixes on that record."

Cobain had interests outside music, particularly photography, but it's almost certain he would not have been able to walk away from songwriting completely. "I think music was pretty much the only thing working for him to give him comfort," says Peterson. "If he could have gotten his act together, he may have dropped out of the music industry and given that pressure the heave-ho and gone off and played with his buddies in a garage with his funds from the first few records." Says Cross: "The drive to create music is totally separate from the drive to release it. He wrote music long before he had any hope of success, and I believe he would have kept doing so."

Putting out music independently has never been easier than it is now, and stepping away from the machinations of the industry as it was in the '90s might have held more appeal for Cobain. "In this era, once you have a brand established, you don't need a label," notes Pavitt. But with that ease comes the rest of Internet culture, and it's uncertain how he might have handled himself. "Could Kurt Cobain and his fragile ego have lived in a world with Yelp reviews and Facebook likes and Twitter? I don't think so," says Cross. "He was not a man for these times."

Instead, his path probably would have been closer to the one chosen by Novoselic, who has led a relatively quiet life outside the mainstream and has focused mainly on local politics. He has released a handful of musical projects, including the bluesy Sweet 75 and a Crazy Horse-esque album as Eyes Adrift with Curt Kirkwood, but none of those seem like they would fit Cobain's profile. In talking to Novoselic, however, it's clear how strong his instincts were to foster his former bandmate's creative path. "I had this habit that I kept up even after Nirvana ended where I would walk by a pawnshop and always look for a left-handed guitar," Novoselic told me. "Kurt was left-handed and needed them, so we would just buy whatever ones we saw."

Back at those park benches, I think about the man who never will be: Kurt Cobain, hunched over that Lead Belly guitar he talked about buying on Unplugged, whispering out melodic folk tunes and barren blues. At 47, he's graying and thicker, but the voice is still there and the spark is still in his eyes.

Cross says he has heard tapes of rough ideas that may get a release someday, but I'm not sure I want to hear them (especially if they're as middling as the unearthed stuff from With the Lights Out). I'll stick to the vision I have of Cobain the reclusive troubadour, producing Daniel Johnston LPs and dropping seven-inch blues covers via Jack White's Third Man Records. Those possibilities are what keep Cobain's spirit in the hearts of all us aging outsiders who still go hard with the lights out.