US firms face tough legal battles in China IP theft

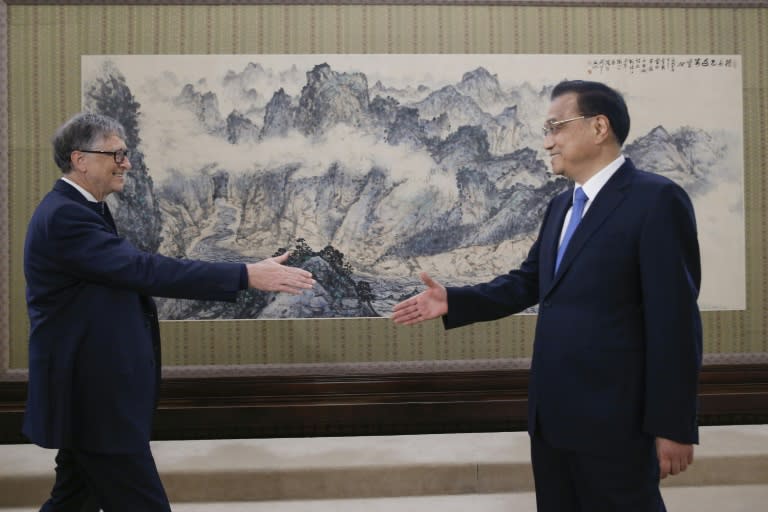

It took a crucial piece of evidence for Microsoft to win one of its numerous anti-piracy lawsuits in China: A computer seller telling an investigator that he could install a Windows 7 knock-off for free. But the US software giant's victory was marred by the paltry compensation ordered by the court, illustrating both progress and challenges for foreign firms defending their intellectual property in China. Premier Li Keqiang pledged this week that China will "strictly protect" intellectual property rights, and special IP courts have been created to hear such cases. But US President Donald Trump has already made up his mind, and was preparing to unveil on Thursday tariffs on a wide-range of Chinese imports for what the White House called "state-led" efforts to steal US technologies. Alibaba's Taobao e-commerce website remains on a list of "notorious markets" put out by the United States Trade Representative. As does the Silk Market in the heart of Beijing, where fake Ralph Lauren polo shirts fly off the shelves. Washington has also long accused Beijing of forcing US companies to turn over proprietary commercial information and intellectual property as a condition of operating in China. - 'Mirror copy' - A survey of US businesses by the American Chamber of Commerce shows IP infringement continues to be a top challenge for some in China, citing inadequate laws and the difficulty of prosecuting cases as the most vexing IP issues. In Microsoft's case in the southern province of Guangdong, the company's lawyers focused on a large computer maker bundling its hardware with a pirated version of Microsoft's operating system in sales on Taobao. Using the name "Bob Jovi", its investigator purchased a computer from MSI's flagship online store in 2015, asking customer service if the machine came with an operating system. According to the court documents, the customer service representative wrote back that he could help install Windows 7: "It's a mirror copy of Microsoft's official operating system, just like the real thing, no fee." After receiving the computer with pirated software, the investigator made two more purchases over the following months to show the bundling was "commonplace" and "sustained", Microsoft argued. While the court ruled in Microsoft's favour, it set damages at $32,000 after finding the total cost of the infringement undeterminable as Microsoft only demonstrated three instances of piracy. Nor did it award Microsoft all of its legal fees. In December, after a two-year process, Microsoft lost its appeal for a larger settlement, leaving the software giant paying out more than it was awarded, the court documents show. "Most important is that the defendant will stop infringing and purchase genuine software," said a lawyer who has represented Microsoft in IP cases, who asked his name not be used. Microsoft declined to comment. The lawyer said it was not cost efficient to sue all infringers but the cases deterred others. - 'Whack a mole' - Microsoft argued its case in a civil court, but China set up special courts in 2014 to handle IP cases in Beijing, Shanghai and Guangzhou. A dozen other lower-level IP tribunals were opened. From 2013 to 2017 the number of IP-related court cases doubled, breaking the 200,000 mark last year, said Tai Kaiyuan, a justice of the Supreme People's Court, noting China now has sufficient IP-related legislation. "We've worked hard to implement them and build the justice system," Tai said, according to state media. Scott Palmer, an IP lawyer who represents US and European companies at Sheppard Mullin Richter & Hampton in Beijing, said China has made "incredible" progress. "There are still problems. There is still infringement, sure, but anyone who watches China and speaks honestly about what they see has to admit it has come a long way," Palmer told AFP. The main area of infringement in China has moved to online platforms like Taobao, where brands face a frustrating game of "whack a mole" to get a range of knock-off products taken down, he said. Laura Wen-yu Young, a lawyer at the IP law firm Wang & Wang, said the IP courts are a "huge improvement" from the past when judges had no relevant training. A trademark case can now take just over a year on average to be decided, compared to having to wait up to four years in the past, she said, though there are still "a lot of improvements needed".