The US transition to digital medical records explained

This is the full transcript for season 4, episode 6 of the Quartz Obsession podcast on your chart.

Listen on: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Google | Stitcher

Read more

Nalis: You know that app on your phone where you have access to all your medical records (past and present), you see all of your appointments, the doctors you’ve seen, your prescriptions, your test results. That same app where your doctor can see your medical history in a couple of clicks. You don’t have it, do you?

Me neither. It’s the year 2023 and in the United States, patient data is mostly digitized, but scattered around a myriad of different sites and apps. Usually one for every provider, each with usernames and passwords to forget and reset.. and forget.. and reset… Today’s medical data portals were born out of a promise of granting easier access to medical records, helping medical professionals and patients find their way in a uniquely fragmented healthcare system.

Instead, they essentially mirrored the fragmentation online. In a way, things aren’t so different from when you needed your doctor to, like, fax over medical records to you or to another doctor, except now it’s done somewhat digitally. Oh, and the majority of this data is handled by one private company: Epic, the maker of MyChart, the most common health data program.

What can possibly go wrong? But how we got here? Why can’t patient portals be easier? Why is there no health portal to end all health portals? And how do countries with less dysfunctional health systems handle their medical data?

Here to try and get answers is me, Annalisa Merelli, Nalis for short, the host of the season of the Quartz Obsession. Today, your chart—of the medical, not astrological, variety.

And here with the answers is Morgan Haefner, an editor at Quartz with a past of reporting on healthcare in the US. Welcome, Morgan!

Morgan: Hey, Nalis, how are you?

Nalis: Let’s get into it, Morgan, beginning from way back. When did humans start collecting medical records, and why?

The origins of collecting medical records

Morgan: That is a great idea. It’s probably one of my favorite parts of this conversation because I think it paints a really good picture about how we got to where we’re at today. So just imagine it’s 17,000 years ago and you are in a cave in southwestern France. That’s where the first documented medical record supposedly is. It pictures someone with a… what is believed to be a wound from an animal, and it’s our first documentation of what having an injury is like. And it really hearkens back to this human want to document things and learn from them. But as civilizations progressed, people started more regularly writing down medical records on clay tablets—think ancient civilizations like those in Egypt, Greece, and Rome—starting to keep more complicated records. And Islamic physicians were known to keep medical records in order to teach the next fleet of physicians that were coming up.

So one of my favorite stories about medical record keeping was the story of Philip Verheyen. And he lived from 1648 to 1710, and he was studying to be a clergyman, but unfortunately had an incident where his leg had to be amputated and used that… I don’t know, if “to his benefit” is the right word… but he got incredibly interested in studying medicine after that, especially anatomy. And the possible myth part of this is he allegedly amputated his own leg, which is quite an interesting story. Whether or not that happened or not, he did become very interested in anatomy and writing down all of these different parts of the human body for others to learn from.

Nalis: And so there’s essentially two aspects to the medical data collection. One is individual health, you know, just kind of tracking how you’re doing over time and improving your own healthcare. But there’s also, you know, as these examples have shown, building up the, you know, wealth of knowledge of medical, the medical field, and kind of, like, helping overall the population be better by, I guess, like, aggregating this data in some forms.

Morgan: Absolutely. Yeah. And it’s very much still a sentiment today and the reason why we have electronic versions of what we used to document on caves and tablets.

Nalis: Before we get straight into the digital world, let’s take a step back. Let’s go to the 90s. If I were an American then and I wanted to look for my health records, what would I have to do?

Health records prior to digitization

Morgan: So there are, believe it or not, some systems that were on electronic medical records back then, but it just wasn’t to the same level that we are today. So you’d be pretty lucky if you could access it on the internet. Back then, it was very much so…think filing cabinets, your data is in a folder with your name on it at the hospital and you would have to get that information in physical format and either fax it over, copy it, etc. So it was very challenging to get your entire medical record and, today, thankfully, I do believe patients have more access to their health information than they ever have before. So that is a huge benefit of this technology.

Nalis: All right, so basically we’ve had 17,000 years minus give or less 20 of writing medical records down on various physical supports, paper being probably the most common until recently, and then we made a huge leap forward into digitization. How did that happen and why?

Why did the shift to digital health records happen?

Morgan: It’s a big story, and I’m gonna start in one spot outside of just the birth of the internet and the digitization of everything, right? I mean, that is a huge player in this as well. But in the US in particular, there is a specific time when we went from a few health systems and hospitals shifting from keeping all this documentation on paper to electronic form. And that happened around 2008. Great year: Flo Rida’s “Low” is blast and outta speakers. Usain Bolt just set the hundred meter world record at the Olympics. But things definitely weren’t as exciting in the electronic medical record field. Only 10% of hospitals in the US were using them and less than 20% of doctor’s offices. But fast forward, six, seven years, and it’s nearly all of them, nearly all hospitals, nearly all doctors’ offices. And so there’s a huge thing that happened and it’s the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health, or it’s called HITECH in the US, was passed. So this regulation incentivized hospitals and doctors to implement these systems and digitize their records. So it helps to get paid to do things. And that was a huge motivator for hospitals and health systems to the tune of about $35 billion in taxpayer money going into this project.

Nalis: All right, so then we get all these incentives and taxpayer money, and the landscape obviously changes a lot from when we had 10% of all providers offering digitized data to the majority of them. What do things look like now, in the US? Like, today when I, you know, try to access my data, what happens?

The current healthcare landscape in the US

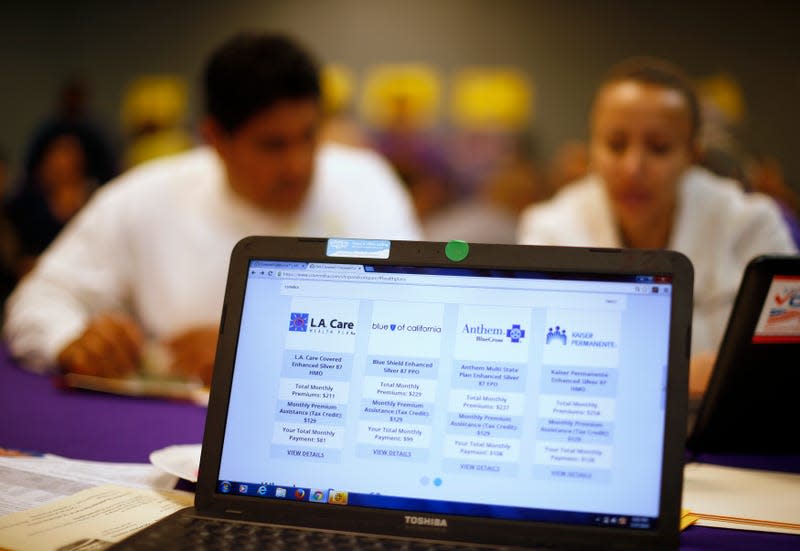

Morgan: Yeah, so say that you need to access the results of a test or whether it’s time to schedule your routine mammogram. Basically what you do is you log into your health provider’s portal or get into their app, so the screen will look different depending on the provider. So say you go to NYU Health, you know, you might see a purple visual identity, whereas if you go to the Mayo Clinic, it’s gonna be teal and blue. But really these differences are purely cosmetic and they all offer the same services. So you can schedule visits, you can check your test results, you can contact your doctors, etc. So let’s say you have a rash and you wanna know how to treat it properly, you can send that picture to your doctor and they can keep tabs on if it’s getting better and what specific treatment might be best for it.

So when you go in for an exam, then, those results get uploaded and you get a notification about them. And unfortunately this sometimes is can turn into a bad situation because you might get the results before your doctor has even been able to see them and interpret them for you, and that can cause a lot of stress and anxiety for patients.

Nalis: All right, so let’s take a bit of a step back into these portals. Like, what does visually look like? Someone who’s not on MyChart and needs to visualize what it is like to be, you know, in the United States and open a health record. What’s that like?

Morgan: You can access your health record on an app or through your computer URL, I would say most people access it through computer. You get an email from your doctor and you open it up—can you hear my cat? She’s, like, trying to get in.

Nalis: No!

Morgan: OK.

Nalis: No, but she is welcome at this point.

Morgan: So it’s basically like any portal, right? You type in your name, your information, your password, and you go into the system and it can vary, like, we were talking about, the cosmetic differences. It can look different between systems, but really you have these icons, right? That, say, you have a, like, a little beaker or something and it’s like “test results,” and then you have a little letter and it’s “messages” and you can click on them and access different services those ways.

And you can also view all of your results on there. So you can click on the icon and it brings up all the different, you know, test results. And some of them look, you know, they’re just like pure data and it’s hard to read them.

Nalis: All right, so we have these portals, but who’s behind them? Like in terms of who provides the technology that they are built on?

Who provides the technology behind patient portals?

Morgan: There’s a couple of big companies in the US that manage this data, and one is Cerner and the other, which is the largest, is Epic. And Epic manages the data of 200 million Americans through its main product, which is MyChart. So when you log on to look at your health information and you see in the little, the URL, “MyChart,” that’s what that’s referring to.

Nalis: OK, so I have, you know, my data online in the portal of the clinic or the hospitals that I took my tests in, or I saw my doctor. Then if I have one in one hospital and then one in another hospital. And say they’re all managed by Epic and MyChart? Can I put them all in one place? Or maybe if I cannot look at them in one place, maybe a doctor, you know, who works at one clinic, can see the results that come from another clinic, kind of automatically.

Morgan: Right. This is the goal. This is what everyone wants, but it’s just not quite that easy yet. And you know, everyone has an electronic medical record for the most part. So physicians and hospital systems are inputting that data, and it’s accessible to them, but the issue is that… Let’s say one hospital is on Cerner, one hospital is on Epic. Those systems are still… they’re getting better, but they’re still not able to talk to each other as well as you think they would be able to in 2023.

And you know, we’re even at the point where people are still having to fax over their medical records. And it just blows my mind that we’re running into those instances because we should be able to have technology that talks to each other better. And it’s a frustrating aspect of this for patients and for physicians as well who do want to make sure that patients are getting their data quickly and safely.

Nalis: Right, because at this point, instead of removing layers of administrative work, you actually add them because you have everything that is required to maintain, you know, safe digital archives, and also the physical faxing and photocopying and whatnot.

Morgan: Absolutely.

Nalis: So you’ve mentioned the ruler of this world, which is Epic. Where does Epic come from? What’s their story?

What does Epic do?

Morgan: Epic is by and large the dominant electronic health record provider in the US. Epic controls health data for 225 million Americans. So it’s huge.

So I’m actually recording this podcast from Madison, Wisconsin, which is where Epic was born. And it started with the CEO, her name is Judy Faulkner. She went to school at UW, the University of Wisconsin, Madison and studied computer science, and, when she was a graduate student, worked with the psychiatry department to create a system that could digitize patient records. So this is all happening in her schooling, and she went on to create Epic in her basement.

And it is a story of a technology coming about at a time when all industries were sort of looking at this rise of the internet and seeing how they can make their businesses better for customers. So you have that going on and then her coming up with this technology. And so Epic was started in 1979 and really started gaining ground in the 1990s. And then the huge turning point I would say for that company was when a massive health system and health insurer in the US by the name of Kaiser Permanente signed a deal with Epic to be their provider for electronic medical records. And that was in 2003. So you have this huge industry leader saying, “OK, we’re gonna go ahead with this company,” and it was a big turning point for Epic.

Nalis: It’s funny. I mean, I say “funny,” but I mean maybe “sexist,” how you hear Bill Gates and Steve Jobs and all the likes being celebrated, and then there is this woman who in the 70s has an intuition that brings her in charge of the medical data of 200 million Americans, but there’s no movie about her. I don’t see her be the role model of, you know, an entire generation. Tell me a little more about her and you know, where Epic and MyChart are at right now.

Morgan: Yeah. Epic gets a lot of press and for interesting reasons. Judy Faulkner herself is a pretty private person. She is a billionaire and runs a company with $3.3 billion in revenue. So you think that she would be more well known, but she’s pretty private. But, that being said, Epic truly has come to dominate the space in the US. They hold about… a little more than 35% of all, market share of electronic medical records in the US with Cerner, the other company, not being far behind, but then the rest is all of these smaller companies. And they grew to dominance for several reasons, a key one being that it’s really expensive to implement this type of technology. And once hospitals made that initial decision to, “OK, we’re gonna invest in it,” there’s this great quote, and I don’t have it verbatim, but I will paraphrase it from Forbes that says something along the lines of, you know, more hospital executives have better marriages with their Epic system than their partners, or something like that. Like, it’s just, like, it’s really hard to get out of these contracts and once you have invested this much money in it, you just can’t really turn back.

Nalis: Of course, part of what makes this all so complicated is that in the US we’ve had an extremely fragmented privatized health system. So basically all of the layers like insurance and benefit administration and all of that, that kind of make everything harder in daily medical life in America, also transfer online, so make everything more complex. Do you have examples from other countries that may have done this better or more simply?

Which countries have better health systems?

Morgan: I think that a country that is doing a decent job with this is Denmark, but it really helps that Denmark has a national health system, and I think countries that have nationalized healthcare have an advantage when it comes to a more centralized space for medical data. So in Denmark, once you turn 15, there is a national portal that actually collects medical information of all citizens. And at birth, Danish people are issued an ID number and they can use it to register for a portal. So compare that to the US. It’s an incredibly different landscape.

A system that I think is really interesting is in Taiwan. In Taiwan, everyone has their own medical card, and this is a newer innovation there where you can access hospitals and providers with this card, and it also carries a brief medical history with you as well..

A country that is more similar to the US in how popular this technology is, is China, actually. China has nearly all of their hospitals use electronic medical records, but the systems are even more complicated than in the US and there are instances when patients actually have to show up with their printed health documents because the hospital’s technology is not talking to each other at all.

Nalis: So when we go back to the US though, the fact that this technology isn’t talking to one another, like how, why is that? So help me understand, because we’ve established that a vast majority of the medical records collected are collected by MyChart. So how come that there is this one company, but then if I look at myself, for instance, I have a handful of logins of different organizations and it’s not as easy as 1, 2, 3 for me to, like, send data from one doctor to another. And I don’t have one place where they’re all in. Like, what’s, what’s the hiccup?

The challenges of fragmented health data

Morgan: Yeah. This is the question that is bugging hospital CIOs. This is why we have a lot of healthcare technology startups in the US that are trying to figure this out. There’s not an easy answer for it. A huge issue is that a company, especially a private company like Epic, doesn’t have a ton of incentive to change its technology to play better with others. Epic isn’t quite a monopoly per se, but they are… it’s hard to not interface with them at all. So you have this proprietary technology that Epic doesn’t want to share because it wouldn’t be an advantage for them to share it. Of course that negatively affects the patient experience when you have folks who have a hard time remembering their passwords, they have four or five different portals. It’s hard to keep track of all of that, and it’s a headache that Epic is trying to fix, but also other organizations are trying to fix too.

Nalis: All right. This part to me is a bit confusing because Epic handles most of the data, so why doesn’t it put it all in one place, even if it comes from different providers?

Why isn’t medical data centralized?

Morgan: For sure. So the reason why, when you go to different health systems, all of that data isn’t being put in one record. So you go to NYU Health, and let’s say you go to the Mayo Clinic, you as the patient, because of regulation in the US, need to be the one that requests that data be shared. Hospitals can’t do that for you unless of course, you know, you have a referral, like, that’s a little bit different. But actually sharing your private medical data, your private medical data, is protected under HIPAA, you know, you’re on the same platform, same Epic, but you go to different health systems. They don’t have the right to, like, share that data among each other.

Nalis: I wonder if it’s like a great business idea for some startup out there. You know, like just get one app where I can put, you know, you ask me for permission to import my health data. Maybe I have them all in one place. I mean, I’m sure someone has thought about it and they just can’t.

Morgan: Oh yeah. I mean, you have companies like Apple and Google that have tried to do this. They’ve tried to launch a personal health record, and they have also found it too complicated.

Nalis: And now let’s get to what I consider, in all of this, truly the biggest elephant in the room. There’s one private company that is sitting on health data for, at least in the US, over 200 million people. Like, how can I be sure that that data’s not gonna get into the wrong hands?

The data security concerns of private health information

Morgan: It’s a scary thing. It is what keeps a lot of CIOs up at night is hackers and the private health information of millions and millions of people getting in the hands of a nefarious party. Epic has worked very hard to put safeguards in place and to have that data secure. And, while no one is bulletproof by any means, there’s a reason why hospitals and health systems choose that platform. A lot of especially small hospitals in the US, rural hospitals and nonprofit hospitals, just don’t have that same capacity. So to secure that data is helpful for them. But it’s a big question, and it’s hard to say whether a private company holds onto this or a government holds on to all the data. There is still one big entity holding onto it and it poses a risk in either format.

Nalis: Of course, all of this isn’t to say that digitized medical data isn’t a good thing. It is, it’s just that it needs quite a bit of improvement before it really makes our life easier. What is the vision here? What do you think it can, you know, eventually do?

How can these systems help improve community health?

Morgan: So to me, a huge positive is: Never before have we had access to such a big aggregate health data of populations. Right? And that is, yes, we were talking about, like, that can be scary for safety and data breaches, but it can also inform medical decisions and even just community health decisions that we’ve never been able to do before. So if you are running a hospital system and have a ton of patients that are coming in for diabetes, you can clearly see, and not on a personal level where you can see their names and addresses and stuff, but you can see that all these people are coming in from the same area. Oh, what’s happening there? It’s a food desert! They don’t have access to a grocery store with lots of fresh vegetables. Instead it’s a fast food region or there is no grocery store. So those are exciting things, I think, that these systems are allowing us to do that can improve health.

Nalis: So, yeah. So going back to what we were saying earlier, this is actually very good for or could potentially be very good for improving populations’ health, even beyond, like, the ease of having one individual’s health record in one place. Like, it really just kind of, like, makes it much easier to get a sense of where a flu outbreak is happening or where a covid outbreak may be happening.

Morgan: Yeah.

Nalis: Before we part, how many patient portal accesses do you think you have now? Like username and passwords?

Morgan: Oh my gosh. I have moved around quite a bit in the past five to seven years, and I would easily nail that at six to seven. Yeah, it’s frustrating! I agree. It’s not ideal.

Nalis: And how strong is your hope that in the near to medium future, you will have one, or that you will not have lost any of them permanently?

Morgan: Yeah, I love this question and I try to be optimistic, but in this situation, it is hard not to get a little pessimistic and disappointed in how slow things take in the American healthcare system. I really would love a future where I could just pull up my phone and be like, “Oh, I have, you know, I’m meeting with my therapist this afternoon and they have already talked to my primary care doctor about this.” You know, I, that’s an ideal that a lot of people in healthcare want and are genuinely working toward it happening within, you know, the next 10 to 20 years? I don’t know.

Nalis: All right on this, uh, realistic optimism note, thank you so much Morgan for being here with us. It’s been a pleasure!

Morgan: Thanks so much, Nalis.

Nalis: And that’s our Obsession for today. The Quartz Obsession is a podcast hosted by me, Nalis Merelli. Katie Jane Fernelius is our producer and George Drake mixes and does sound design. Music is by Taka Yasuzawa and Alex Suguira. Additional production support provided by multi-platform editor extraordinaire Susan Howson, research wizard, Julia Malleck, and audience genius, Ashley Webster. Shivank Taksali and Diego Lasarte are our natural born sound engineers.

Special thanks to Quartz deputy email editor Morgan Haefner, who is likely already resetting a MyChart password right now.

If you like what you heard, please review this on Apple Podcasts or wherever you listen to your podcasts. Tell your friend about us, then head to qz.com/obsession to sign up for Quartz’s Weekly Obsession email and browse hundreds of interesting backs.

I think I said tell your “friend” about us.

Support for this episode comes from EYGS LLP. © 2023 EYGM Limited. All Rights Reserved.

More from Quartz

The US will pilot a program to renew H-1B visas domestically

More than half of US nursing homes are unprofitable—and it's about to get a lot worse

Sign up for Quartz's Newsletter. For the latest news, Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.