Voices: Is this a trigger warning I see before me?

Warning: the following article may contain distressing words. Because it’s about trigger warnings at the theatre, especially contemporary productions of Shakespeare. Avert your eyes now if you must. Everybody ready? Right – read on, Macduff…

Shakespeare, besides being widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language, was also a fatphobe. We know this because the Royal Shakespeare Company has slapped a trigger warning on its new production of The Merry Wives of Windsor, where audiences are advised before curtain-up about the bodyshaming of the portly comic creation, Sir John Falstaff.

For this, the RSC has been roundly criticised – but saying as much would probably be deemed fatphobic.

Asked for comment by a Sunday newspaper, acclaimed Shakespearean Dame Janet Suzman said: “This fashion for trigger warnings, as if an audience were as helpless as a tiny child, is both insulting and silly. Who is such an idiot that they would pay good money to go to a Shakespeare play – repeat: play! – and expect to be left unmoved?”

Suzman is but the latest Bardolater to join the devilish holy fray against the infantilising practice. Even the RSC’s former head, Gregory Doran, has railed against it, saying: “Don’t come if you are worried. If you are anxious, stay away.”

In February, Ralph Fiennes said it was time to scrap trigger warnings in theatres so that audiences can engage more fully with productions and be “shocked and disturbed” by violent or sexual themes in a play.

When told of theatreland’s growing vogue for trigger warnings, Dame Judi Dench said: “Do they do that? It must be a pretty long trigger warning before King Lear or Titus Andronicus. I can see why they exist, but if you’re that sensitive, don’t go to the theatre.”

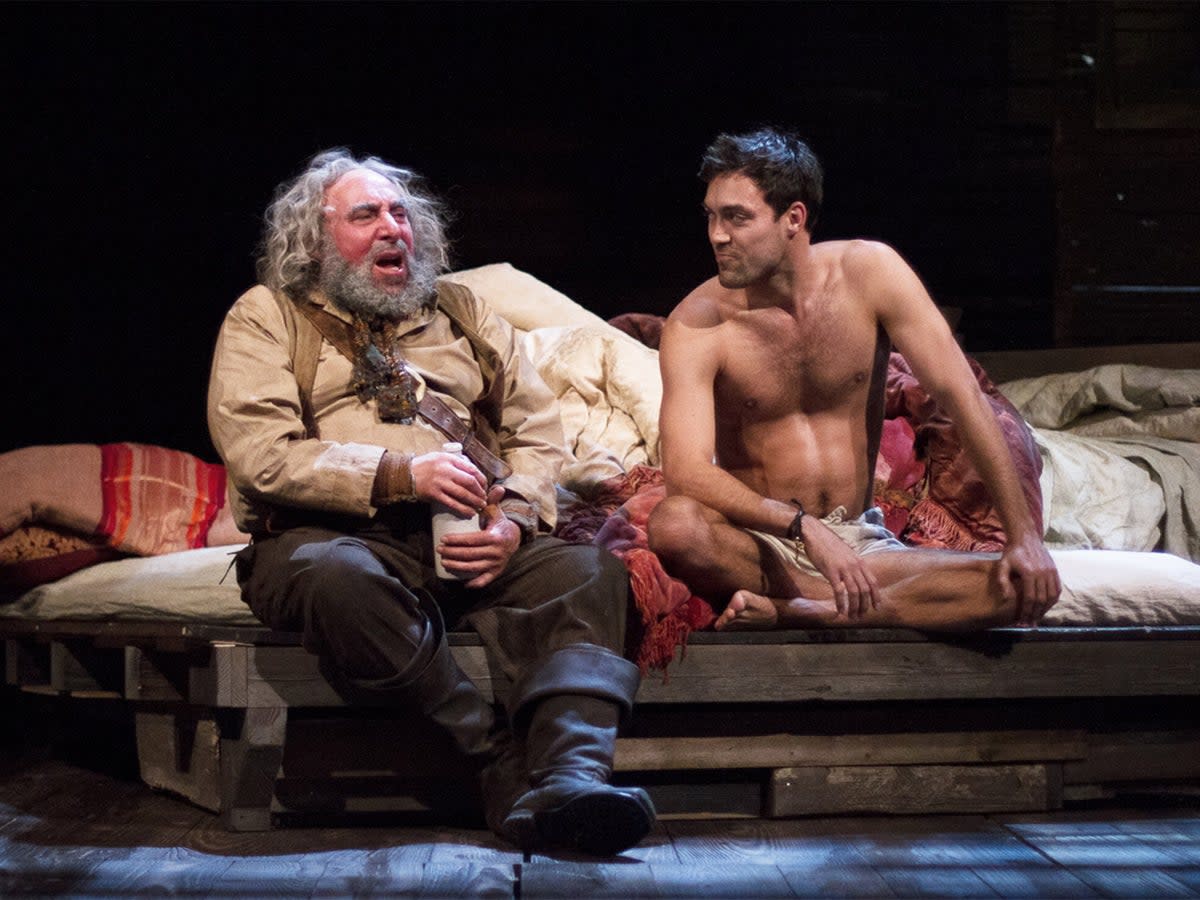

Sir Ian McKellen – himself currently starring as Falstaff in a fat suit, in a West End production – has called trigger warnings in theatres “ludicrous”, adding: “I quite like to be surprised by loud noises and outrageous behaviour on stage.”

Certainly, trigger warnings have become so silly of late to have rendered the very thing redundant. The dreaded placard notice in the foyer, which was once purely practical – such as when announcing the use of strobe lighting or loud noises, which can induce epileptic fits – is now an opportunity for a progressive director to parade their holier-than-thou credentials before you’ve taken your seat.

The @TheRSC Royal Shakespeare Company is warning audiences that ‘The Merry Wives of Windsor’ contains bullying and fat-shaming. Spoiler: ‘King Lear’ contains scenes that some people may find upsetting.

— John Simpson (@JohnSimpsonNews) June 10, 2024

The threshold for what is deemed triggering seems to sink lower by the day. Now, anything that might leave your average grievance Olympian literally shaking – I’ve heard of pre-performance apologies being made for strong language, dated attitudes, discussions of bereavement, on-stage smoking, “weapons, including knives”, “distressing scenes of music, family and romance” and even “theatrical fog” – is worthy of a warning.

It’s all about time. In January, a new production of Antony and Cleopatra at Shakespeare’s Globe in London came with a “content guidance” warning (the phrase “trigger warning” itself was cancelled for being triggering). Audiences were told it contained “depictions of suicide, scenes of violence and war and misogynoir”. Unlucky the patron who was still busy googling that when the “phones off, please” notices went up.

Being warned that what you’re about to watch might be a bit edgy gives the game away – a bit like going to a pub that needs a bouncer on the door. You already know how sad a night you’re in for.

For his part, Fiennes wondered if today’s audiences have gone soft: “Shakespeare’s plays are full of murder and full of horror,” he told the BBC’s Laura Kuenssberg, “and as a young student and lover of the theatre, I never experienced trigger warnings like: ‘Oh, by the way, in King Lear, Gloucester’s going to have his eyes pulled out.’”

The 61-year-old actor has made a career out of characters who slowly, quietly unsettle his audiences – in Schindler’s List, playing a commandant who used concentration camp prisoners for target practice; as the unassuming serial killer in The Silence of the Lambs prequel Red Dragon. To put warning messages on either of these films – the latter, a horror film; the former, about one of the worst chapters in human history – would be artistically redundant.

Fiennes’s most exquisite performance for me was his 2022 West End staging of TS Eliot’s epic poem, Four Quartets – an impressive feat of recollection as much as a thrilling, pin-drop theatrical experience. I don’t recall a foyer notice warning that it contained references to war, loss and immolation. But perhaps the audience had something to do with it: there weren’t many under-60s in.

It’s easy to blame young people – but when impresarios are desperate to inculcate new generations into the theatre habit, all-must-have-trigger-warnings is part of a readiness to bow and scrape to “sensitivities”. At a time when West End tickets are routinely in three figures, it is commercially prudent not to alienate even the fussiest paying punter.

Of course, the trigger warning habit has germinated in academia – on university courses that warn adult undergraduates that the novels of Jane Austen contain “toxic relationships and friendships”, that Robert Louis Stephenson’s novel Kidnapped includes scenes of abduction, and that the classic children’s bedtime story Peter Pan might prove “emotionally challenging”.

And it’s not that new audiences are unhypocritical in their demand for trigger warnings. The Book of Mormon, the brilliant musical by the creators of South Park, attracts a younger-than-average crowd with the promise of blasphemy, near-constant swearing, jokes about Aids, FGM, Hitler’s sex life and baby rape. Trey Parker and Matt Stone don’t believe in trigger warnings. All the times I’ve seen the show, most people are too busy laughing or picking up their jaws from the floor to take any offence.

I wish theatres would stop pandering to the worst kind of patrons and instead make an example of them. The only sign I want to see before a performance is a reminder to turn your phone off, not just on silent – ideally, one backed up with a muscular threat of immediate ejection if you don’t. I would bet money that the kind of people who “need” trigger warnings about theatrical violence or fatphobia would think nothing of bringing in hot food to the stalls, or having a quick scroll on their Instas during a performance, the glow from the screen lighting up the dress circle.

If these blasted trigger warnings are here to stay, where do we draw the line? Which theatre is going to be the first to ban applause, to protect those people triggered by clapping, and instead request that jazz hands be used at the curtain call? Is giving a standing ovation disablist?

There – everyone happy now?