Where are the punks? Dua Lipa’s Camden docuseries completely misses the point

The first question any potential producer of a docuseries about Camden should ask themselves is: will Graham Coxon do it? If the answer is, “No, but Dua Lipa is involved,” they should immediately shut down production and funnel the budget towards a Dua Lipa tour movie instead.

Not so the new Disney+ series Camden. For much of the 1990s, Blur guitarist Coxon was basically Camden incarnate, holding court from his permanent corner of the Good Mixer pub, the bespectacled fulcrum around which London’s entire Britpop scene revolved. Over four 45-minute episodes, however, he appears for just one second, and only in static photo form. Hilariously, it arrives during a lengthy section that tries to make out that this borough’s Britpop era was pretty much all about Oasis because Noel Gallagher (who did agree to take part) had a flat there for a bit.

Therein lies the folly of a series with its heart almost in the right place: ie the swanky new Koko members bar rather than the back room of the Marathon. Lipa, one of the series’ executive producers, spent several years living here as a child and recorded her first YouTube songs in a Camden flat aged 15, but – such is the major pop star mindset – she seems far more concerned with lauding the biggest names that lived and played here than getting under the gritty fingernails of the place.

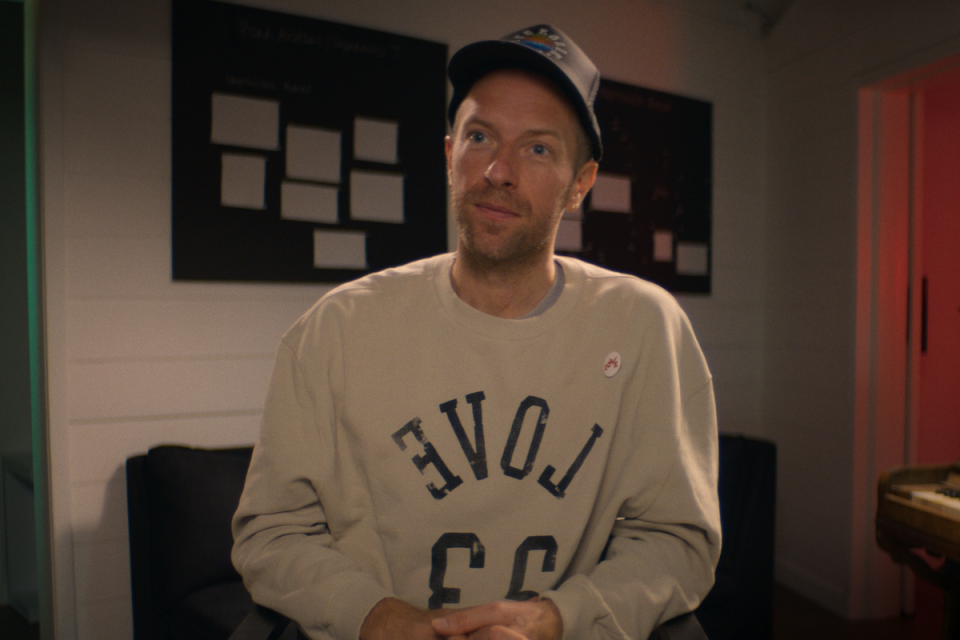

Checking her WhatsApp contacts, the producers seemed to have decided that much more relevant than Coxon to the history of London’s most snake-bitten quarter is the fact that Coldplay played their drum kit-free first gig at the Dublin Castle (a story that Chris Martin beamingly recounts alongside grainy footage). Or that Little Simz emerged from the Roundhouse’s new talent facilities, where she first saw those quintessential NW1 legends Jessie J and Rizzle Kicks.

Judging by Lipa’s breathless narration, to her the fact that Madonna, Prince, and Bruno Mars have played these chip-smeared streets is far more telling of the area’s counter-cultural relevance than, say, Sheep on Drugs at the Camden Palace’s indie mega club Feet First. The Notting Hill of rock docs? Let’s just say, the only punks we see in this documentary are glimpsed from the safety of the back of a town car. No one dares venture into the goth hive of the Devonshire Arms.

Camden’s intentions are undoubtedly honourable. Vertigo-inducing rents have long driven most young artists east to Shoreditch and Dalston, from whence the capital’s artistic zeitgeist was last seen departing for Peckham and Brixton around 2017. And ever since, although Camden has remained the city’s major live music hub, it’s hard to deny that it’s become something of a pastiche of itself: a tourist-friendly, open-air museum of alternative cultures. Rather than hunt out the hottest new band (they’re all south of the river now), Camden is where you go to see wild, free-roaming cyberpunks in their natural habitat, or wield the same wonky pool cue that Jarvis Cocker once used.

Many things of note happened here, but it’s been some time since it was “happening”. It’s heartening, then, that today’s major breakthrough stars want to honour the capital’s grubbier cultural crucibles – the Dublin Castle, the Good Mixer, the Barfly (now the Camden Assembly) – and shine a light on Camden’s contemporary significance. No one is more enraptured with the place than Doncaster-born convert Yungblud, who gets closest to Camden’s crux when he posits: “When a hub of people who are frightened to be who they are gather in a place and get taught it’s OK to be who they are, it becomes a place of fearlessness.”

But as with Lipa playing Glastonbury or Halsey headlining a Reading and Leeds stage, the problem here is what we might call the mainstream-ification of subculture kudos. Major chart acts consuming institutions of underground credibility; pop eating not just itself but all the cool stuff, too.

For Camden, it’s a process that began circa 2006, when Amy Winehouse seamlessly merged NW1’s hedonistic attitude with retro soul music. Her death made her the iconic millennial queen of Camden, and it’s a high-profile angle that the series dives for like a hawk. Straight from a promising start in which Suggs talks us through the Madness-led origins of Camden’s pub gig culture, it takes the first episode all of 17 minutes to get to Winehouse’s story as if, more than any other, it now defines the place. Meanwhile, Lipa pops up with increasing frequency, driving past old flats and haunts, or being interviewed in legendary venues, seeming rather desperate to make Camden 2024 all about her – or at least the Camden adjacent A-list set.

From there, the series quickly becomes a parade of potted histories of any major act the producers could secure who have ever been north of Euston. Plenty of crowbarring is done to get the biggest names possible into Camden’s story. The Brixton-reared Soul II Soul get a substantial chunk of screen time for having once filmed a video on Chalk Farm Road. Much is made of Visage singer Steve Strange’s New Romantic nights at the Camden Palace, but not so much of the scene’s origins at the Blitz Club in Covent Garden. Public Enemy and the Black Eyed Peas, too, make appearances to reminisce about the odd gig they played at the Jazz Cafe.

The documentary’s fatal flaw is to assume that the borough’s spirit lies in its biggest success stories and most tragic downfalls

Most random of all, here’s Nile Rodgers talking about the time he went to a Camden record shop after a Roxy Music gig and got the idea for Chic. Yet The Clash, the band whose late-Seventies base in the market arguably sparked the entire Camden scene, are but briefly represented in a short picture montage set to a cinematic ambient crescendo. Permissions presumably denied.

There are some worthy revelations here, particularly in episode three when Gilles Peterson, Norman Jay, and long-term residents The Roots lift the lid on the acid house and hip-hop evolutions that took place in the Electric Ballroom and the Jazz Cafe. There’s also good work on The Libertines in episode two, despite their Noughties scene being rooted at least as much in Whitechapel as the Hawley Arms. But Camden’s fatal flaw is to assume that the borough’s spirit lies in its biggest success stories and most tragic downfalls.

In fact, Camden is about every unsigned band that ever played the Monarch to Steve Lamacq and a dog. Every dreamer that handed out a soggy flyer outside the Underworld. And every emo teenager down under the canal bridge trying to convince themselves that the “drugs” they bought outside the tube station were doing more than ridding them of intestinal worms. That nobody asked ubiquitous Nineties Camden scenesters Menswear to take part in the series demolishes entirely the credibility of the enterprise.

Dua Lipa may be “of” Camden, but to accept that she and her big-name contacts list “are” Camden would be to abandon yet another cornerstone of our rich alternative music history. Enough of your mainstream-ification – deliver Camden: Coxon’s Cut, then we’ll talk.

All four episodes of ‘Camden’ are available to stream now on Disney+