Alito’s ‘Godliness’ Comment Echoes a Broader Christian Movement

It’s a phrase not commonly associated with legal doctrine: returning America to “a place of godliness.”

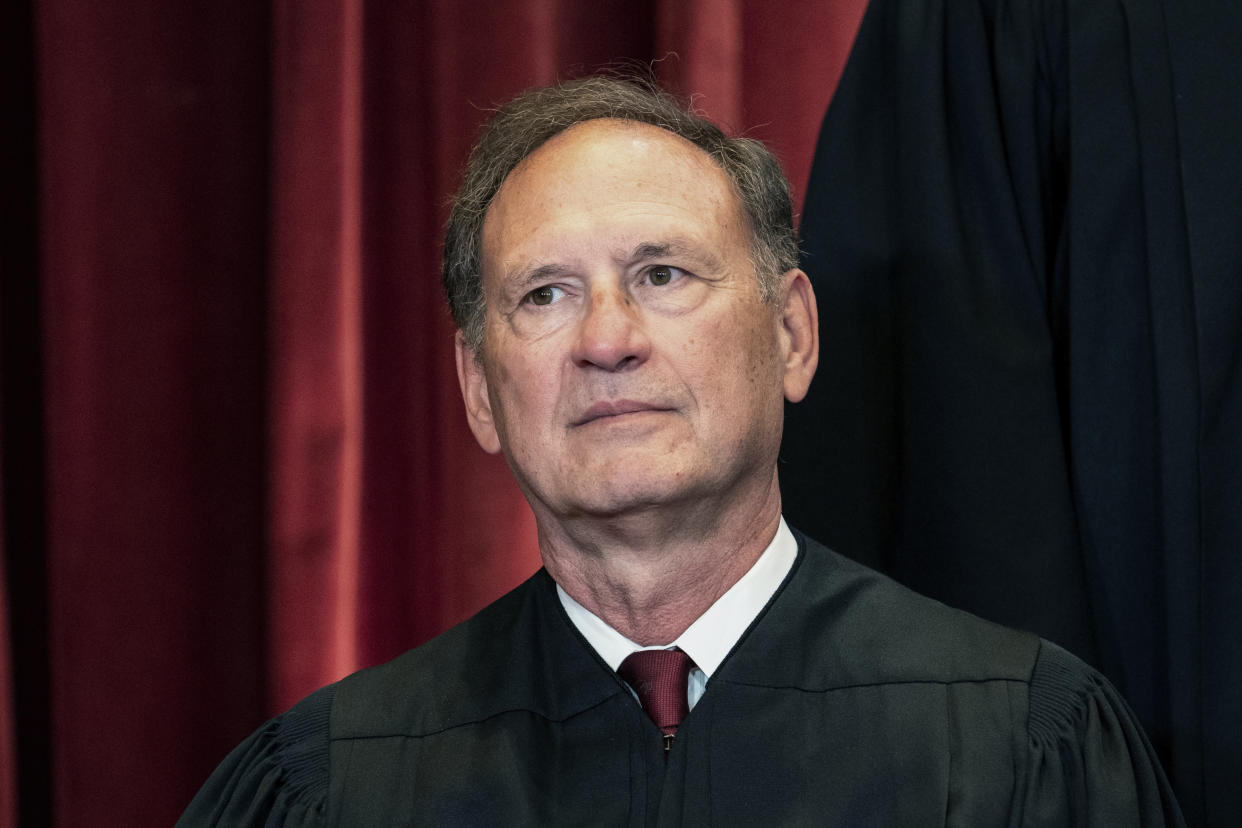

And yet when asked by a woman posing as a Catholic conservative at a dinner last week, Justice Samuel Alito appeared to endorse the idea. The unguarded moment added to calls for greater scrutiny by Democrats, many of whom are eager to open official investigations into outside influence at the Supreme Court.

Sign up for The Morning newsletter from the New York Times

But the core of the idea expressed to Alito, that the country must fight the decline of Christianity in public life, goes beyond the questions of bias and influence at the nation’s highest court. An array of conservatives, including antiabortion activists, church leaders and conservative state legislators, has openly embraced the idea that American democracy needs to be grounded in Christian values and guarded against the rise of secular culture.

They are right-wing Catholics and evangelicals who oppose abortion, same-sex marriage, transgender rights and what they see as the dominance of liberal views in school curriculums. And they’ve become a crucial segment of former President Donald Trump’s political coalition, intermingled with the MAGA movement that boosted him to the White House and that hopes to do so once again in November.

The movement’s rise has been evident across the country since Trump lost reelection in 2020. The National Association of Christian Lawmakers formed to advance Christian values and legislation among elected officials. This week in Indianapolis, delegates to the Southern Baptist Convention, the largest Protestant denomination in America, are voting on issues like restricting in vitro fertilization and further limiting women from pastoral positions.

And in Congress, Mike Johnson, a man with deep roots in this movement and the Alliance Defending Freedom, a conservative Christian legal advocacy group, is now speaker of the House.

Now, Supreme Court justices have become caught up in the debate over whether America is a Christian nation. While Alito is hardly openly championing these views, he is embracing language and symbolism that line up with a much broader movement pushing back against the declining power of Christianity as a majority religion in America.

The country has grown more ethnically diverse and the share of American adults who describe themselves as religiously unaffiliated has risen steadily over the past decade. Still, a 2022 report from the Pew Research Center found that more than 4 in 10 adults believed America should be a “Christian nation.”

Alito’s agreement isn’t the first time he has embraced Christian ways of talking about the law and his vision for the nation.

Shortly after the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade two years ago, a ruling for which Alito wrote the majority opinion, the justice flew to Rome and addressed a private summit on religious liberty hosted by the University of Notre Dame. His overarching concern was the decline of Christianity in public life, and he warned of what he saw as a “growing hostility to religion, or at least the traditional religious beliefs that are contrary to the new moral code that is ascendant.”

“We can’t lightly assume that the religious liberty enjoyed today in the United States, in Europe and in many other places will always endure,” he said, referencing Christians “torn apart by wild beasts” at the Colosseum before the fall of the Roman Empire.

A flag associated with support for a more Christian-minded government was also flown at Alito’s beach home, according to reporting from The New York Times.

The “Appeal to Heaven” flag, or Pine Tree flag, is a symbol from the Revolutionary War period, but it has gained new traction among conservative Christian supporters of the “Stop the Steal” movement, some of whom carried the flag during the Jan. 6 attack on the U.S. Capitol. Alito said that his wife, Martha-Ann Alito, was “solely responsible” for flags flown at his homes.

At the same event last week where Alito spoke in support of “godliness,” his wife said she wanted to fly a “Sacred Heart of Jesus flag” to push back against a neighborhood Pride flag, according to more secretly recorded comments. Alito, his wife said, asked her to refrain from putting it up after the recent flag controversy.

The Times has not heard the full unedited recording and has reviewed only the edited recording posted online, after the woman who recorded them, a liberal activist, declined to send the Times the full recording.

In Catholic tradition, the Sacred Heart of Jesus is a mystical sign of the divine love of Jesus for humanity, often symbolized with an image of a human heart wrapped in a crown of thorns, like the one Jesus wore when he was crucified.

It dates to a French saint born in 1647 named Margaret Mary Alacoque, who was paralyzed as a child and had visions of Jesus revealing his Sacred Heart to her. She inspired a tradition of devotion and an official Catholic holy day, the Feast of the Sacred Heart. Leonard Leo, the conservative legal activist and longtime head of the Federalist Society, named his late daughter Margaret Mary, who had severe spina bifida, after the saint.

But the resonance of the Sacred Heart goes beyond simply an abstract religious concept, just as the Pride flag does. Each is notable for the vision of America that they symbolize, and the different visions of marriage, family and morality that they represent. For one slice of America that celebrates LGBTQ+ rights, June is Pride Month. For another devout, traditional Catholic slice, June is a time to remember the Sacred Heart.

Trump, for his part, has long courted conservative Christians, tapping into their sense of rejection in a steadily secularizing society. In 2016, he made what became a famous campaign promise that if he were elected, “Christianity will have power.”

Even now, as Trump tries to present himself as more moderate on abortion, breaking with some of his most stalwart supporters, he continues to court their support.

He spoke via video message to a gathering at the Southern Baptist Convention on Monday, where he promised a broader Christian coalition “a comeback like no other” should they vote for him. Democrats, he said, were “against your religion in particular.”

The group he addressed, the Danbury Institute, is a coalition of Christian churches and conservative activists that aims to see abortion “eradicated entirely” in America.

“These are going to be your years, because you’re going to make a comeback like just about no other group,” Trump said. “I know what’s happening. I know where you’re coming from and where you’re going. And I’ll be with you side by side.”

c.2024 The New York Times Company