Calm before the storm: behind the scenes at Tyson Fury's training camp

At the Top Rank gym in Las Vegas, down a little side street called Business Lane, the door is sealed shut by a dustbin that stops it blowing open to the world outside. In this secluded space the old Detroit gang prepare for work on one of the last mornings left before Tyson Fury faces Deontay Wilder for the WBC heavyweight world title. Their first fight, in December 2018, produced an epic battle. Fury’s superior skills seemed to have won him the decision but being knocked down twice by Wilder meant it was called a draw. Both men remain unbeaten, after 43 bouts for Wilder and 30 for Fury, and heavyweight boxing has a compelling decider between two riveting characters.

Andy Lee, Fury’s cousin and new assistant trainer, is a former world champion middleweight and one of boxing’s most incisive analysts. In the gym he plays a recording of an iconic fight – Roberto Duran’s defeat of Sugar Ray Leonard in Montreal 40 years ago this summer. Duran and Leonard were both fighters of huge ego, with their skill supplemented by ferocious will, and a fascinated Fury watches as he skips rope.

Related: Redefining the 'strong man': Tyson Fury praised for openness on mental health

Contemporary boxing finally has a bout to echo those halcyon days and reach a mainstream audience again. Despite his clear belief Fury will win the rematch in Vegas, and he has predicted that Wilder will be stopped early, Lee is admirably open about why this fight is on a knife edge.

“Both men have huge belief in themselves,” he says. “They almost have this God-given right they’re going to win. You can analyse all Tyson’s and Wilder’s words and tactics but you can’t see what’s inside either man. [The late] Emanuel Steward (Lee’s former trainer whose memory binds the Fury camp together] used to say champions were built from the inside. Their mental strength, toughness and resilience is deep inside them. Both Wilder and Tyson have all these qualities.”

Lee pauses as the rope whirrs and Fury’s feet dance with light delicacy for a giant heavyweight of 6ft 9in and 270lb. “There is still something unquantifiable about this fight,” Lee says softly. “We can’t know for certain who will be the stronger inside. Who will get distracted? Who will dig deeper inside themselves? Who will crack first? I believe Tyson will win but it’s like Duran against Leonard. Who could have predicted exactly what would happen?”

Duran won the first encounter but in their Las Vegas rematch five months later, in November 1980, he turned away in humiliating surrender, saying “no más”. Whenever boxing pits two fighters of immense ego and will against each other something elusive and mysterious rises up. In this rematch, the most unquantifiable facet is the Detroit connection between Fury and his new trainers Javan ‘SugarHill’ Steward and Lee.

As they get ready for work on a Tuesday morning the minds of all three men drift back to Detroit and the Kronk gym, where they first hung out together 10 years ago. The Kronk was run by Emanuel Steward, who helped 40 boxers become world champions. One of those was Lee, the Irish middleweight who won the WBO world title in 2014. SugarHill, Emanuel’s nephew, also worked in his great friend Lee’s corner. Fury had flown to Detroit on a whim four years earlier to sample the Kronk’s gritty magic. The bond between this trio, now plotting a way to overcome Wilder’s murderous punching, was forged in the Kronk.

“Emanuel asked my dad a year before if I would go to Detroit and train with him,” Fury remembers as SugarHill wraps his massive hands. Fury looks animated as the memories tumble through him. “But my wife was pregnant and it wasn’t the right time. Then I had another fight and thought: ‘If I don’t go now, I’ll never know.’ If I didn’t go to Detroit that time, I knew my life would never turn out the way it was meant to do. So, aged 21, I jumped on a plane to Detroit. I didn’t let anyone know I was coming. I flew into Detroit airport, first and only time I’ve been there, and I got a yellow cab and said: ‘Can you take me to the Kronk gym?’”

SugarHill cocks a surprised brow. “Why didn’t you call me?” he asks.

Related: Boxing quiz: Deontay Wilder, Tyson Fury and the history of rematches

“The taxi driver finally found the Kronk and I said: ‘Give me five minutes,’” Fury remembers. “I was going in to see if I was welcome. If I wasn’t I was going straight home. I walked in. SugarHill’s in the ring and I said: ‘Is Emanuel around?’ Sugar said: ‘Who are you?’ I told him: ‘I’m Tyson Fury, the next heavyweight champion of the world.’”

That brashness surprised SugarHill. “I didn’t know what to think,” the trainer admits. “He had hopes of being a world champion and he’s this huge guy with a strange English accent. I wasn’t sure what to expect. I wanted to watch him box to see if he could live up to everything he said.”

Fury flexes his wrapped left hand, appreciating Sugar’s work with the tape and gauze. “I’ve always been an outspoken, controversial character,” he says. “I’ve never been the shy type. I suppose they weren’t used to seeing this because Americans look at the British as reserved. But I was louder than any American in the Kronk. They thought: ‘OK, we’ve not seen this before, but we’ll roll with it.’”

Emanuel Steward welcomed Fury into his home. He’d done the same a few years earlier when he asked Lee to move from Limerick to Detroit so he could train him at the Kronk. “Manny didn’t know me,” Lee chips in from the apron of the ring. “I could’ve been a murderer but he made me feel at home. Manny gave me the bedroom next door to his.”

Fury nods. “It was the same with me. Andy was away when I arrived and straight from the start Manny insisted I stay with him. He said I could stay in Andy’s room. He was a very welcoming old man. Even though I hadn’t met him before, I felt like I knew him 25 years. I’d never had my hands wrapped before fights. Manny took half an hour wrapping these hands every day – just like Sugar’s doing it.”

I’ve sat in the dressing room before a fight with Lee and watched him wrap the hands of his brilliant protege, Paddy Donovan, and there is something hypnotic about the Kronk way. It’s just as easy to get caught up in Fury’s memories of Detroit. “Emanuel used to take me, Sugar and Andy to this special place. It was all boarded up on the outside. But when we went in it was a restaurant and bar full of former Motown singers, and people who didn’t quite make it to Motown. Everybody was singing and it was unbelievable. Best singers I’ve ever heard.

“I said: ‘I’ll sing a song.’ I took the mic and sang Eric Clapton’s Wonderful Tonight. Everyone fell in love with me. I was only a young kid but I was happy getting up in front of this crowd and singing. It felt very natural because I was always very high on me.”

Related: Tyson Fury holds the edge over Deontay Wilder before rematch

His confidence and exuberance hid the mental trauma that nearly destroyed him a few years later. But Steward said Fury was one of the three biggest characters he had met in boxing – alongside Muhammad Ali and Naseem Hamed. “I only went to Detroit for three weeks,” Fury says nonchalantly, “but I left a mark. Like a dog pissing on the wall.”

Fury left his biggest mark in the ring. “Me and Andy tore up the Kronk one day. I sparred every heavyweight and cleaned up. Andy sparred and beat up everyone under that weight. The old fellas at the side who were ex-champions couldn’t believe it. They were shouting: ‘Oh my God, I never thought I’d see the day. White boys taking over the Kronk!’”

Steward looks up. “It wasn’t just two white boys, it was two Gypsies. That’s different. We recognised that, because black and Gypsy fighters feel they have been discriminated against. They have a chip on their shoulder, and always want to prove themselves. Black and Gypsy fighters have that same determined attitude forged in adversity. It’s like when Andy moved to Detroit from Limerick [in 2005] no one but Manny knew who he was. He was just this white kid. Then his boxing, and his similarities to the black community, shone through. That won him approval and made him one of us. Tyson has the same qualities and there’s definitely a bond between black and Gypsy fighters.”

The self-proclaimed Gypsy King is as proud of his heritage as Lee – an unusual figure in boxing who has acted in a Chekhov play in Dublin while sharing his intelligence in an understated way. Their decision to work with Steward stems from a belief that returning to these Kronk roots could make a decisive difference for Fury against Wilder.

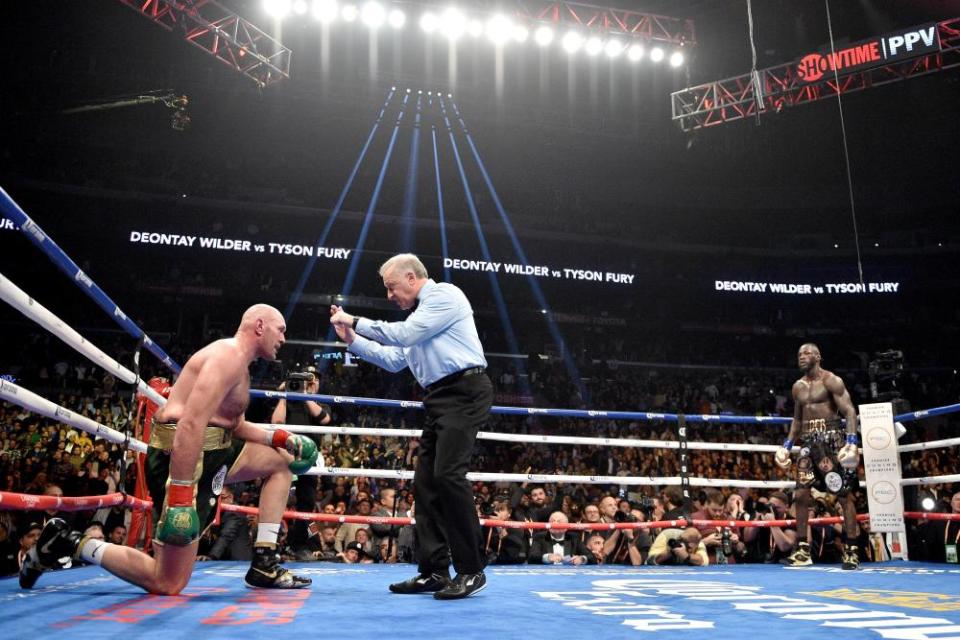

It might seem strange that Fury would change his awkward and elusive style as he bamboozled Wilder for long stretches of their first fight. The old Kronk strategy, of seeking the knockout above safety-first tactics, might also seem a worrying gamble against a devastating puncher. But Fury is one of the world’s most unconventional boxers, and a daring and unpredictable man who believes he can do pretty much anything. He proved that in the first fight when, having been knocked out for a few seconds in the last round against Wilder, he showed spooky powers of recovery to haul himself up and be in complete control of his amazed opponent once the final bell rang.

Ben Davison, the young trainer, did fine work in lifting Fury from the grip of depression to the brink of beating Wilder. But he has been replaced by SugarHill Steward. Davison’s emotional connection with Fury is obvious but Steward has been brought in to instil key technical changes and, in essence, to teach the Gypsy King to throw his punches with more authority. Watching Steward teach Fury behind closed doors is instructive. A routine session becomes a boxing lesson in closing down angles, footwork and the best way to throw a punch.

Related: Tyson Fury has to channel Muhammad Ali … with his feet not his mouth | Kevin Mitchell

It’s surprising that Fury, who calls himself the linear heavyweight champion of the world after he shocked Wladimir Klitschko to gain control of all the belts in 2015, should need such basic tutelage. But Fury should be respected for his desire to improve in the ring. He admits it has been an adjustment and that initially, despite having fought professionally for 11 years, he felt like “a novice” when he began working with Steward seven weeks ago.

“I felt like I’d never had a fight. It was weird but I knew it would come right. I just had to practise everything Sugar taught me. We haven’t worked on what I’m naturally good at. We’ve worked on what I’m not naturally good at and improved. Old tricks of the trade.”

An hour later, when Fury, Steward and Lee leave the ring, the education continues. Fury watches the next recording Lee has chosen. The second bout between Aaron Pryor and Alexis Arguello in September 1983 lights up the gym while Lee offers the full context. Pryor had stopped Arguello in the 14th round the previous November, in a bout eventually voted the fight of the decade. For the rematch Pryor brought in Emanuel Steward to replace his controversial trainer Panama Lewis.

In his underpants, while towelling himself down, Fury points excitedly to Steward in the corner: “There’s Manny!”

The Gypsy King’s boxing knowledge is fallible and Lee is politely non-committal when Fury suggests Oscar De La Hoya is the greatest fighter in history. But, sitting with Lee and Steward, after Fury has waved goodbye, there is gravitas. Lee, who was instrumental in advising Fury that he should add Steward to his camp, says of the legendary trainer, who died eight years ago: “Emanuel is no longer here, but he would have been the perfect trainer for Tyson. The closest thing to Emanuel now is Sugar. The fundamentals of boxing – correct balance, correct punching and ring craft – are not taught now. So that’s why I suggested Sugar because I knew those things would benefit Tyson.”

Steward leans forward. “We’re doing it the way Emanuel taught us. Emanuel would say: ‘Hey, I’m not doing anything special. Just the basics everyone should learn the first day they walk into the gym.’ Today, everybody wants entertainment. They’re bored by the basics. They want to see 35 combinations, which is never going to happen. You just need to master the basic scenarios. Tyson is humble enough to want to get better.”

But isn’t it difficult to change some elements of a 31-year-old fighter’s technique with just seven weeks of preparation before the biggest fight of his life? “It’s not difficult when you work with a person who wants to learn. I’m just teaching him the fundamentals. Emanuel taught me that if you correct those things you can catapult a fighter to another level.”

Some people believe Fury has switched from Davison to Steward to save money. Eddie Hearn, Anthony Joshua’s promoter, suggests that there has been acrimony in the camp. Yet, during my two days with Fury’s team, in Vegas and Henderson, the atmosphere seems serene and good-humoured. “I’m smiling every day,” Steward says of all the rumours. “I’m smiling even when it’s windy and cloudy outside.”

Tyson's balance has improved. He can knock Wilder out this time

SugarHill Steward

As for all the speculation that Fury aims to stop Wilder early, and so risks being knocked out himself, Lee talks calmly. “Wilder has real power and that’s a great thing. But that power’s not so great when it’s used against you. Sometimes you can wait for that big punch too long. Next thing you know you’re getting outboxed and you’re losing rounds. Or you might throw that big shot and get countered, and next thing you know you’re underground. Your momentum and your own power’s been used against you.”

Is Fury hitting harder now? “Yes,” Steward says simply. “His balance has improved. With improved balance comes greater power. By punching at the same time, and countering him before he lands, he can definitely knock Wilder out.”

For the first fight Lee was ringside in Los Angeles, commentating on BBC radio with Mike Costello, and afterwards “I went to see Tyson in the dressing room. I was just amazed by him and everything he had done in overcoming the weight loss and depression. The fact they scored the fight a draw was OK. What he had done to get to that position was remarkable.”

When it is Steward’s turn to remember where he was that night, he says: “I was in hospital.”

I look at him quizzically and he says: “Quebec City. Adonis Stevenson against Oleksandr Gvozdyk. Same night as Fury-Wilder I.”

On 1 December 2018, Steward trained Stevenson, a formidable light-heavyweight, a violent and rugged man who lost his WBC world title and almost his life when he was knocked out in the 11th round by Gvozdyk. Stevenson suffered brain damage and slipped into a coma. It’s a chilling reminder of the danger all boxers face.

I tell the two trainers that, of all Fury’s revelations, the one that has stayed with me longest is his story about how his wife, Paris, sat down on their hotel bed in LA after they returned from the Wilder fight. She took off her make-up, removed her false finger nails and began to sob. She told her husband she could not bear to watch him go through the same ordeal again.

The two boxing men know that the Gypsy King will face another brutal test on Saturday night.

We meet again the following afternoon, at a gym in Henderson, where Fury undertakes a strength-and-conditioning session. He is still friendly but quieter than the previous morning. We sense the looming danger. Fury reveals that, before their first fight, he and Wilder exchanged regular texts – full of kidology and glee about how much money they would make together. But, since Fury shocked Wilder by getting up from seeming oblivion, the American has not responded to any texts from the Gypsy King. Has he got under Wilder’s skin?

“I’m not sure,” Fury says. “I don’t read much into all that. I don’t get involved in mind games. I’ve seen Wilder at press conferences and he seemed OK. He knows what he’s got to do. I know what I’ve got to do. That’s it. No more, no less.”

Lee adds: “Tyson’s a gentleman. People don’t see that. A big part of my job is just to talk to Tyson. Our conversations about boxing are relatively small but the conversation about life, about his past and his future aspirations, are much deeper. Special people come along every now and then – like Elvis Presley, David Bowie or James Brown. Muhammed Ali is the one in boxing. I would have loved to be in his presence. Imagine being alive in those times, with those guys. But here, with Tyson, we’ve got someone special as well. It’s a privilege to be here.”

How do he and Steward feel about being in the corner on a tumultuous night in Vegas? “I think both Tyson and Wilder have improved since the first fight,” Lee says. “They’ve faced each other and they both know how much better they need to be to win.”

He looks at his friend from Detroit. “Andy’s been involved in a lot of big fights.” Steward says. “I’ve been around a lot of big fights. Tyson’s been around. Ain’t nothing new for any of us. It’s the same old shit.”

Lee smiles. “Yeah. The fight happens to be in Vegas but it could be anywhere. We’ve all got one aim – just to win the fight.”