COMMENT: Unequal access and self-censorship reign in Singapore journalism

There are plenty of Chinese proverbs extolling the virtues of listening to your elders and respecting authority. In this regard, I have decided to take the advice of veteran journalist PN Balji, a renowned figure in Singapore journalism and occasional Yahoo News Singapore contributor.

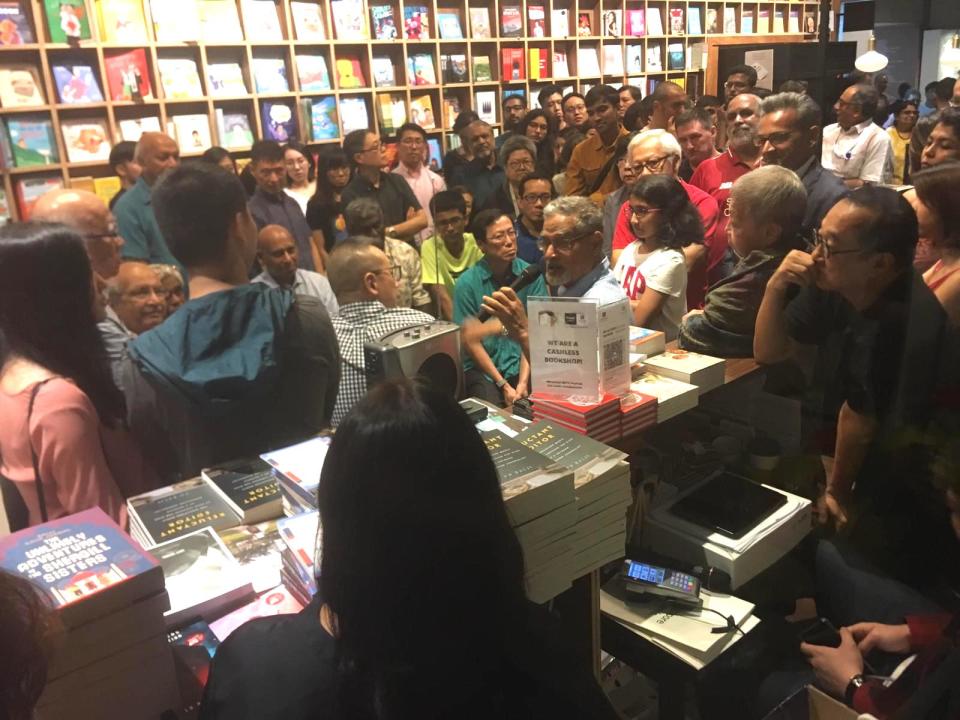

At the official launch of his book “Reluctant Editor” on 14 June, the 70-year-old noted, “Singapore journalists hardly write stories about journalism. Many of them take these stories to the grave.”

"Reluctant Editor" largely covers Balji's time as editor of The New Paper and Today, with many behind-the-scenes stories of the government's often contentious relationship with the mainstream media. It topped the non-fiction bestseller list at Books Kinokuniya the week it was released.

The 70-year-old paints a portrait of a thin-skinned government that often reacted defensively to negative coverage and was unafraid to resort to strong-arm tactics. Jobs were literally at stake, and more than one journalist felt the wrath of the authorities.

On one occasion in 1981, senior editors at Singapore Press Holdings (SPH) were summoned to a press conference with then-Transport Minister Ong Teng Cheong. There, Ong demanded that the editors reveal their source for a Straits Times story about impending bus fare hikes. The editors declined.

Fast forward 38 years later, with the proliferation of social media and alternative news sites, has the government changed its approach to the media? No. It has simply gotten smarter and much more sophisticated about it.

At 38, I haven't quite reached Balji's level of gravitas or knowledge. But I do have some stories to tell based on my 12 years of experience in the media industry.

A caste system for press access

As I have previously written, unequal access for mainstream media (MSM) and alternative news outlets in Singapore is a well-established fact. SPH and Mediacorp outlets are given priority for the most important press releases, speeches and event invites.

It is not unusual for accredited outlets like Yahoo News Singapore to be sent press releases hours after the MSM outlets have broken a story, or to be told that certain high-profile events are reserved for "local media only".

On one occasion, when we requested an advance copy of the National Day Rally speech - probably the most important political speech of the year - we were given the runaround by senior government officials who all had the same excuse: "I don't have it." Meanwhile, MSM reporters had obtained the speech the day before.

In this day and age, why is the MSM still accorded first-mover advantage over other media outlets, thus enabling it to shape the narrative first?

'We cannot facilitate your request'

Without the equivalent of a Freedom of Information Act, which enables Americans to request the disclosure of information by the US government, local government agencies are often less than forthcoming, particularly on sensitive topics.

In April, while Yahoo was pursuing a story about maid abuse, a request was sent to the Manpower Ministry for facts and figures on this issue. We received a one-liner in reply, "We’re unable to facilitate your queries."

In an era where public accountability is more important than ever, why are government agencies still empowered to simply fob off reasonable requests for information from the media?

'What is your agenda?'

Then there is the practice of having your access cut off, often with no notification or explanation. Think of it as being ghosted by a Tinder date.

In March this year, in response to a peculiar incident where Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong's eldest son was filmed by a stranger who gave him a lift, the police revealed the man's antecedents. To date, the driver has not been charged with any offence.

I then did a follow-up story with quotes from lawyers who questioned why the police had potentially prejudiced any case against the driver by publicising his previous brushes with the law. Upon receiving my request for a quote, a police spokesperson called our editor and posed the classic question, "What is your agenda?"

After giving the assurance that our “agenda” was only to practise good journalism, we were promised an official response, and therefore held back our story. Two days went by without word from the police.

When Yahoo informed the police that we were going ahead with the story, we received a bizarre request: could we not mention that we had asked the police for a response?

Shortly after the story was published, something inexplicable happened: Yahoo stopped receiving police press releases about impending court cases.

After verifying that this was not down to crossed wires or some broadband outage, we were informed by a police source several weeks later that Yahoo had been taken out of the police mailing list following an internal "annual review" of access for media outlets.

Self-censorship

During an interview ahead of his book launch, Balji said self-censorship is "the greatest sin in Singapore journalism" and that it is "worse than what it used to be before".

Sometimes, it seems that the MSM does not even need to be pressured to play ball. In late May, news broke that Li Huanwu, a grandson of Lee Kuan Yew, was marrying his male partner in South Africa but none of the MSM outlets covered it.

Did it have anything to do with the fact that Li is the son of Lee Hsien Yang, who is embroiled in an ongoing dispute with his elder brother PM Lee over their former family home at 38 Oxley Road or that the conservative segments of society are against gay marriage?

There was also inertia among MSM outlets in their coverage of PM Lee’s recent comments that Vietnam had previously invaded Cambodia, which triggered strong criticism from Singapore’s two Asean neighbours.

Perhaps it also had to do with the ever-present fear of reprisal. Just consider that in 2017, the Official Secrets Act was invoked against a Straits Times reporter over the leak of a confidential HDB project.

The broad powers that the anti-fake news laws have granted ministers to determine what constitutes a falsehood mean journalists have to tread carefully more than ever.

If the journalists themselves are afraid of doing their jobs, how is the public being served? If the journalists do not speak up, then who will? In a country whose institutions are so thoroughly dominated by the ruling party, where will the checks and balances come from?

It only feels appropriate to end this commentary with a quote from Balji. Addressing a group of young journalists recently, he asked pointedly, "Are you afraid of losing your job? If you are, then you shouldn't be in this profession."

I couldn't agree more.

Related story:

Lee Kuan Yew made journalists 'look behind their backs': veteran journalist PN Balji