Plight of abused foreign domestic workers who seek justice and shelter in Singapore

SINGAPORE — Hartatik* was in her third month of employment in Singapore in 2017 when the Indonesian domestic worker began to experience constant physical abuse by her employers.

Her ordeal coincided with the tumultuous phase of the married couple’s relationship, as the young Singaporeans struggled to look after a toddler and a two-month-old infant.

The Lampung native, now 36, became a convenient punching bag.

Frustrated with her husband, Hartatik’s female employer took it out on her by attacking her limbs, sometimes with a pan, or stomping on her.

A small mistake by Hartatik, such as preparing baby milk that was too hot, would set the employer off.

In retaliation, scalding water would be poured on Hartatik’s body. On occasions, the couple would use soiled baby diapers to hit her, leaving her face smeared with faeces.

One particularly brutal incident left Hartatik with a deformed left ear. The couple had pulled and hit it repeatedly, leaving it swollen and infected. They brought her to a doctor a week later, where she was made to lie about her injuries.

For the next three months, Hartatik endured daily torture before her female employer kicked her out of the house for an innocuous error.

“I can't stand the pain, remembering all these memories,” the mother of a teenage boy told Yahoo News Singapore tearfully in Bahasa Indonesia. “I wanted to run away but I was scared.”

Hartatik’s case is another sad statistic of reported maid abuse in Singapore, where she was among the 253,800 foreign domestic workers (FDWs) living and working here as of December last year, up 23 per cent from 206,300 FDWs in 2011.

Last year, 28 maid abuse cases were filed, the highest in five years, according to the State Courts. Between 2014 and last year, 107 cases were filed. In the same period, sentences were passed in 55 cases.

In recent months, several cases of abused FDWs were in the media spotlight, including one described by the prosecution as “arguably one of the worst of its kind” in Singapore.

The perpetrators, a married couple who were convicted two years ago for abusing an Indonesian maid, Fitriyah, had assaulted another helper from Myanmar and made her eat her own vomit.

Last month, Chia Yun Ling, 43, was jailed for three years and 11 months and ordered to pay Moe Moe Than, $6,500 in compensation. Tay Wee Kiat, 41, was sentenced to two years’ jail and ordered to pay her $3,000 in compensation.

In their earlier case involving Fitriyah, the couple appealed last year for their jail terms to be lowered. In a landmark decision, the High Court ruled that Tay’s original jail term of 28 months was “manifestly inadequate” and raised it to 43 months.

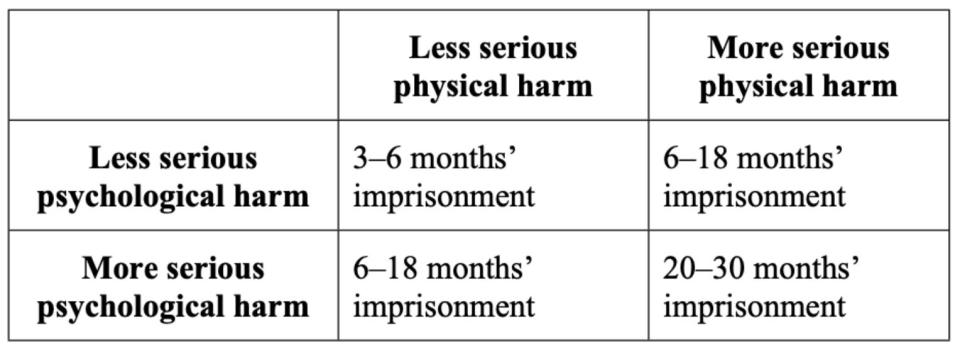

Crucially, the High Court outlined a new sentencing framework for such cases, factoring in the emotional trauma that abused FDWs go through.

Before these cases go to court, claims of abuse are first investigated by the police or the Ministry of Manpower (MOM). Even so, it takes years before cases, if applicable, are heard in court.

The ministry declined to respond to media queries on the number of claims of abuse it received and number of resolved cases last year. It also declined to comment on the number of ongoing investigations.

Seeking sanctuary in shelters

A number of abused FDWs, such as Hartatik, seek sanctuary in shelters while they assist in investigations and wait to be re-employed at an average of $450 to $600 monthly.

Last year, over 1,170 FDWs were housed in shelters run by non-government organisations Humanitarian Organisation for Migration Economics (HOME) and Centre for Domestic Employees (CDE). Both also run 24-hour help lines.

Hartatik was one of 373 FDWs - a surge from 141 in 2017 - housed at CDE’s shelter last year.

Cases like hers, where physical abuse occurred, averaged about 13 per cent of over 2,400 cases - including hotline calls - that the CDE handled over the past three years, said executive director Shamsul Kamar.

Meanwhile, HOME case manager Jaya Anil Kumar said that its shelter sees about 15 to 20 runaway cases per week, housing over 2,500 maids in the last three years.

The top common complaint leading these women to seek shelter was overwork, according to a report by HOME and Liberty Shared released in January.

Siti*, 25, an FDW from West Java, Indonesia, told Yahoo News Singapore that she had to work for 15 hours starting at 6am daily for her male employer in Singapore.

Every night from 12 to 2am, she was forced to massage her employer’s legs and back before she could go to sleep.

“If I say I don’t want to do it, he will threaten not to give me my salary. I also had to work at my employer’s siblings house every Sunday or Saturday,” she said in a mix of halting English and Bahasa Indonesia.

Siti, one of 800 who sought shelter at HOME last year, returned home to Indonesia in July.

The HOME-Liberty Shared report also called for the inclusion of domestic workers under the Employment Act (EA) to ensure that basic labour rights, such as working hours, sick leave, limits on overtime and notice periods, among others, are regulated.

The workers’ exclusion from the Act “leaves them highly vulnerable to abuse. Current provisions under the Employment of Foreign Manpower Act are not equal to those under the EA and are too vaguely worded to offer reliable protection”, it added.

Laavanya Kathiravelu, an assistant professor at the Nanyang Technological University’s School of Social Sciences, noted the existing recommendations under the Act for “adequate rest” are vague and not easily enforced as these workers work within private spaces.

As such, the amount of rest they are given is typically left up to negotiations with employers.

There is also a misguided perception that domestic work is not “real” work and this has led to workers not getting time off or enough rest, she said.

Jaya stressed that more domestic workers - often untrained - increasingly undertake caregiving responsibilities for elderly patients, which often translates to “round the clock care”.

In a written reply to a parliamentary question on Tuesday (7 May), the Ministry of Social and Family Development revealed that there were 34,200 working residents in Singapore, aged between 21 and 64, living with at least one elderly family member aged 65 and above and at least one young child aged below 13 as well as at least one FDW last year.

“One thing we would like to see is better matching of domestic workers to the right kinds of employers,” said Jaya. “Employment agencies have a part to play in that and employers should be forthcoming in the workers’ responsibilities.”

Shamsul urged the MOM to monitor employers whose FDWs seek constant transfers from.

“Such employers may need to be sent for counselling and deferred from hiring another FDW until the MOM has had an interview to ascertain that they are ready to hire again,” he said.

Range of complaints by maids

Other top complaints listed in the 2019 study include emotional abuse - such as verbal insults, intimidation and threats -, salary-related claims, illegal deployment and inadequate provision of food.

In a 2017 report on food security, in which about 30 Indonesian domestic workers in Singapore were interviewed, Charlene Mohammed, a researcher at the University of Victoria, found that almost half went hungry regularly.

Most involved in the study were forbidden to eat until after employers had eaten, she wrote in her report. They were often fed food that their employers had refused to eat, such as leftovers, stale or mouldy food, and biscuits.

In March, armed with renewed optimism, Siti came back to Singapore to work for a second employer.

Unfortunately, the Muslim was forced to consume pork by a Singaporean employer who eyed her every move at the dining table during their meals together.

“Ma'am says that there is only pork to eat. She gets angry if I don’t eat it,” said Siti.

When her employer was not around, the close monitoring of Siti’s movements was taken over by CCTVs installed everywhere in the house, including in the workers’ room.

To prevent Siti from running away, her employer made her wear her clothes while keeping the former’s belongings in a box inside the locked master room.

Just three days into her employment, Siti ran away in tears and sought shelter at HOME for the second time. “I couldn’t take it anymore,” she said.

Charlene said that she had come across cases like Siti’s, where workers were forced to consume food they are not comfortable with for religious reasons.

“The controlling of food consumption often results from the employer’s fear of losing status as the head of the household. It’s a dehumanisation practice to keep workers at a lower status,” she said.

Such treatment, where laws are not “flagrantly breached”, can also affect the mental well-being of these workers, said Jaya.

An Institute of Mental Health (IMH) spokesperson said that the institution sees FDWs from time to time who were admitted due to mental health issues or suicide attempts.

IMH consultant Dr Jared Ng shared that FDWs often come from a background of “adverse socio-economic conditions” without support networks in a foreign country.

So when abused, this often leaves them at a high risk of developing psychological issues, such as depression, or post-traumatic stress disorders, he added.

“These impairments can last a long time, even when they return home to their own countries of origin. In severe cases, they may develop thoughts of self-harm and suicide,” said Dr Ng.

Called her a prostitute

It only took two months into her job before things soured for Maruat*, 27, who started working for a foreign couple - her 4th employer in Singapore - in August last year.

The domestic worker from Mizoram, India, had dropped off her employer’s son at his music school. She was supposed to return to fetch him after the classes were over.

Unbeknownst to her, the school was closed that day. Left alone, the boy had to borrow a handphone from a stranger to call his mother.

“She (called back and) said I should not treat my son like a dog to be dropped off,” Maruat told Yahoo News Singapore in English.

Following the incident, her employer became prone to outbursts, sometimes, threatening to call the police on her, and other times, throwing a random object such a bag or a bowl at Maruat.

“All the time, I would apologise and say sorry,” said the mother of a five-year-old boy. “I wish she would talk to me nicely. I am a mother and a human being too.”

Maruat’s breaking point came when her employer insulted her by saying that she wanted to “show off her sexy body” to neighbours and that she was prostituting herself in Orchard for $10, in front of the couple’s children.

Her employer then exposed herself to Maruat. “I was very scared. She started removing her pajama bottoms and showed her underwear to me. She then opened up my shorts,” said a visibly shaken Maruat.

“My employer said, ‘If I want, I can do anything to you. This is my house. If I want to see, I can see.’”

Fined for no good reason

Maria*, 31, was made to wash her Singaporean employer’s feet, several times a day, as well as help wear her socks and shoes.

Whenever the Filipina made a small mistake, she would incur the wrath of her employer, who is in her 50s. Once, Maria was kicked in the chest.

For three years, Maria and a fellow domestic worker woke and slept at the same time as her employer. Her days were erratic and could start at 4pm or 2am after a four-hour rest.

One of her daily tasks was to mop the floor of her employer’s three-storey house 10 times, regardless of how clean it was.

“She will threaten that the whole house has (over 20) CCTVs so I cannot escape the job,” said the mother of two young boys in English.

Maria had $500 deducted from her salary by the employer for a faulty door just because she was the last to lock it.

On another occasion, she was paid $200 less for allowing National Environment Agency (NEA) officers to do a routine check in the house. The officers had issued a fine to her employer for a violation due to the presence of mosquito larvae.

Maria managed to get back over $1,000 that she was owed with the help of the CDE and the MOM.

Her work permit and passport, which were withheld by her employer for the entire duration of her employment, were also returned. “I never see them in three years,” said Maria. “I cried every day to myself. It’s not good if I keep changing employers so I tried to shut the scoldings out.”

The withholding of personal belongings such as passports is often encouraged by agencies who advise employers to curb the movement of their domestic workers, said Prof Laavanya.

The compulsory security bond has also caused some employers to develop “paternalistic notions” and view the FDWs as incapable of making their own decisions about their mobility or finances, she added.

Luck in Singapore ran out

Hartatik and Maria are currently happy working with their new employers, who give them adequate rest and time off for interviews with the authorities pending investigations against their previous employers.

During her 10-month stay at the CDE, Hartatik was slowly encouraged to go back to work. “(If I stay) at CDE, I won’t have any income for my children. Now that I’m starting work again, I feel relieved,” she said.

Her wish now is for her abusers to receive “a justified sentence”. “I hope no one else will receive the same fate as me,” she added.

The punishments for causing or allowing the death of or serious injury to vulnerable victims, including domestic helpers, have been enhanced, following the passing of the Criminal Law Reform Bill on Monday. Offenders, who commit the act or fail to protect the victim, can be jailed up to 20 years, fined, and/or caned.

“Such errant employers should also continue to be shamed in the media,” said Prof Laavanya.

Despite her ordeal, Maria plans to continue working in Singapore for the next decade to save up enough for her children - two boys aged 9 and 7 - and complete construction of a family house back in Camarines Sur, her hometown.

Her current monthly salary in Singapore is about six times of what she would earn back home. “I endured my former employer’s abuse because my happiness is my salary,” she said.

Maruat and Siti were not as lucky.

The case against Maruat’s former employer, who was investigated for allegedly insulting her modesty, was dropped by the police.

Left in limbo for six months at HOME’s shelter with no job, Maruat was made to return home early Friday, less than 40 hours after she found out about the “surprising and unfair” verdict.

“I have been to around seven interviews with potential employers. But with the time needed for investigations and my ‘track record’, they are wary of hiring me,” she said. “Why would they pick me? There are so many ladies with no problems queuing in the maid agencies.”

“I come from a poor family and I don’t want my son to be a labourer. I can feed him (if I work in India) but I can’t give him a future,” she added.

The various financial, language and immigration hurdles that these FDWs face in resolving their abuse cases could cause them to lose faith in the Singapore legal system, and “accept less than satisfactory settlements of their civil claims or just drop their claims altogether”, said June Lim, managing director of Eden Law Corporation.

“The FDWs always want to go home, the process can take up to three to four years to complete, they are traumatised by the abuse, and their families need the money. Poverty is the reason why they came to Singapore to work in the first place,” said Lim, also an ambassador for Law Society Pro Bono Services.

The sense of indifference that Maruat feels about Singapore now is a stark contrast to the excitement that she first felt when she saw a TV advertisement on job opportunities in Singapore back in Mizoram.

While she has not ruled out a return to Singapore, she is planning to work as a domestic worker elsewhere.

“I feel like my luck here has run out,” said an emotional Maruat.

As for Siti, two days after her interview with Yahoo News Singapore in early April, she embarked on a flight back home to where her young twins, a pair of two-year-old boy and girl, were waiting for her in West Java. No police reports were filed against her employers.

“For me, this is the most painful and hardest thing I've ever experienced. Because not once but twice, I faced employers who were mean to me. I don’t ever want to come back to Singapore,” she said.

*All names have been changed to protect their identities.

Related stories:

Parliament: Not beneficial to foreign domestic workers to be brought in for short-term help

Paralegal jailed 10 months for breaking maid's fingers, causing bleeding in both eyes

Woman jailed for pinching and punching maid, threatening her with knife

Couple jailed for abusing Myanmar maid, ordered to pay compensation

Woman who permanently disfigured maid with iron and pliers jailed 2 years 7 months

Trial begins for maid accused of brutally murdering employer in Telok Kurau home