Deceased former journalist inspires others to donate bodies to science

Sathi Devi, widow of the late PM Menon, and her daughter Jayanthi Menon (right) Photo: Nicholas Yong

Some four decades ago, journalist Punnappilly Madhava Menon decided to donate his body to science to be used for medical research. In the wake of his passing from pneumonia earlier this month, friends and family members have been inspired to do the same.

The 85-year-old’s younger daughter Jayanthi told Yahoo Singapore that at least 10 friends have reached out to the family to make the same pledge. “The messages I got was that ‘we have decided’,” said the 51-year-old artist and former lawyer. “Others also came to see us to find out how to go about it.”

One of them is her close friend Sujja Menon, 46. The housewife, her husband and their 18-year-old son have all been inspired to commit their bodies to science. “I had heard about it, but never took it seriously until Jayanthi mentioned it when Uncle fell very sick,” said Sujja, who added that her mother and aunt have also pledged their bodies.

“I’m hoping that this story will go further and inspire people to sign the form and not cremate their bodies, when the medical community can use them for research.”

Cadavers for medical research

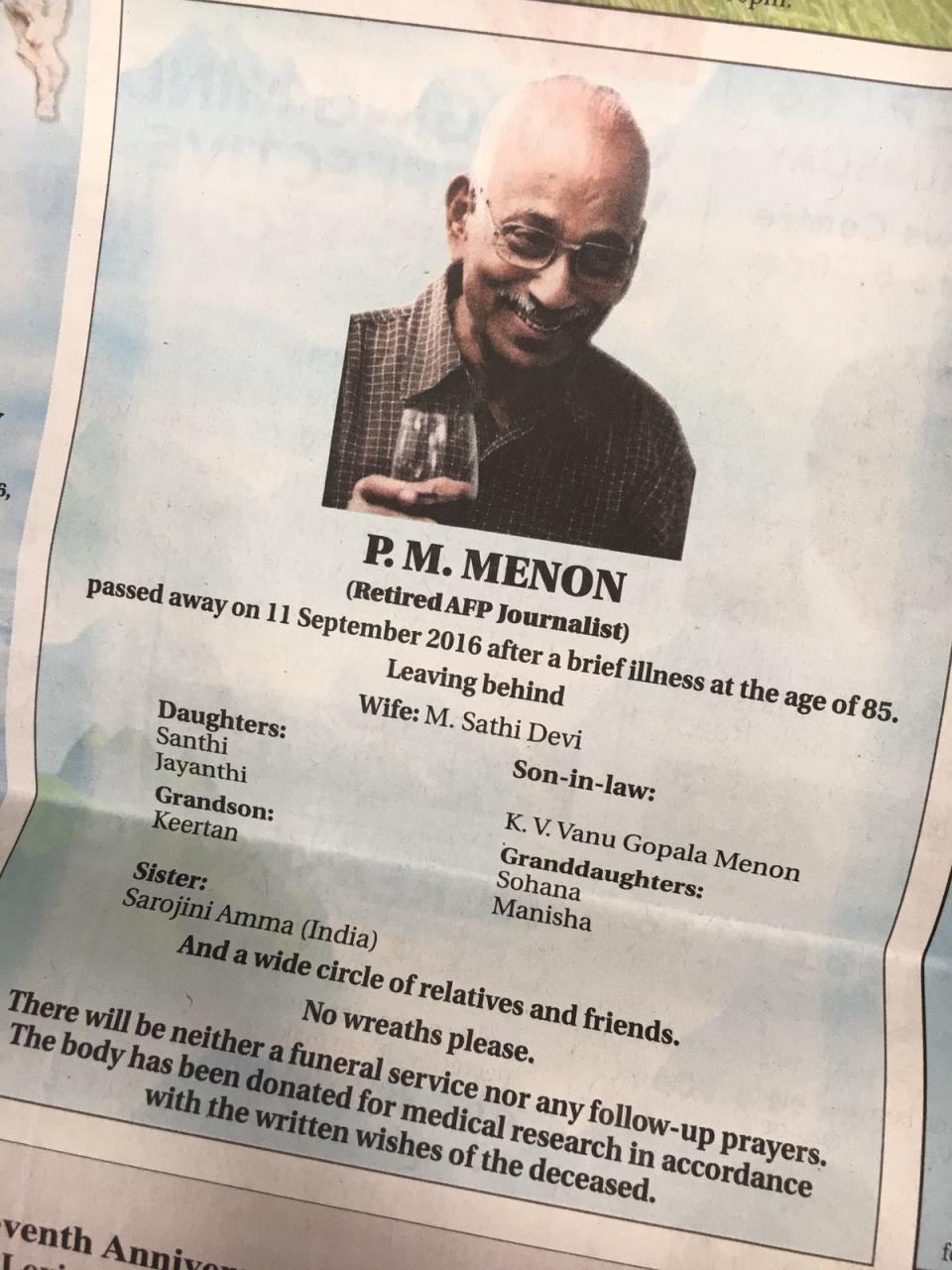

P.M. Menon’s obituary in The Straits Times. Photo: Nicholas Yong

The Medical Therapy Education and Research Act (MTERA), which legislates organ donation, was first enacted in 1972.

In response to queries from Yahoo Singapore, the National Organ Transplant Unit (NOTU) said that as of August 2016, more than 2,000 people have pledged their bodies to be used for medical teaching and research since the Act took effect.

Research on each donated body takes between six months and four years. Upon completion of the research, the donated bodies are cremated and the ashes returned to the families.

These bodies are assigned to different medical institutions such as the Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine (YLLSOM) at the National University of Singapore, where Menon’s body was sent.

According to Associate Professor Ng Yee-Kong of YLLSOM’s Department of Anatomy, the school has received some 18 bodies so far this year. Given that YLLSOM takes in some 300 medical and 54 dentistry students each year, this still translates to a shortage.

Prof Ng said that students are taught to treat donors, or ‘silent mentors’ as they are called, with respect and dignity.

“Silent mentors (like) Mr Menon, they are so selfless, giving their body as last gifts for medical education and research. When students can practice on actual bodies, they can appreciate the intricacies and the relations between the different layers of the tissues and the orientations of the bodies, as well as variations between individuals’ bodies.”

A principled man

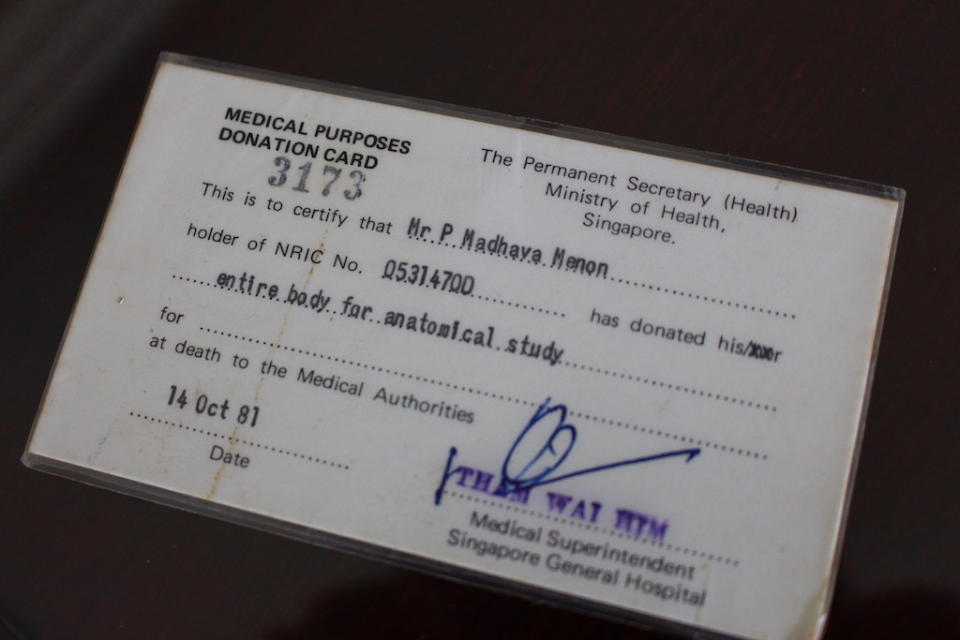

P.M. Menon’s original organ donor card. Photo: Nicholas Yong

Family members remember Menon as an erudite, stubbornly principled man with a strong work ethic who spoke six languages. He came to Singapore from the Indian city of Kerala in the 1950s and became a citizen.

Menon, who spent 33 years as a sub-editor with French news agency Agence France-Presse before retiring in 1990, took great pride in being a journalist, and meticulously filed every story he had worked on.

In his personal life, the father of two and grandfather of three was an affectionate and jovial man who made people laugh. His grandnieces called him ‘Happy Mutachan’, or ‘Happy Grandfather’ in Malayalam.

His older daughter Santhi said Menon was an avowed atheist, but loved talking about religion. “He could quote from the Bible, the Koran, the Bhagavad Gita,” said the 56-year-old, who is based in Perth and works in project management consultancy.

Jayanthi, who is married to Singapore’s High Commissioner to Malaysia Gopala Menon, added with a smile, “He was very tolerant. We (Jayanthi and her sister Santhi) both went to convent schools and I used to say my Hail Marys before my meals. I just respected him so much because he never forced it on us.”

While Menon was in ill health in recent years, he began arranging his affairs even before, having passed a folder of documents to Jayanthi in 2011. It included his organ donor card and a personally written obituary, which even had options (“passed away after a brief/prolonged illness”) that she could cross out.

Leaving a legacy

P.M. Menon and his wife Sathi Devi used to take a photo for their wedding anniversary every year. Photo: Nicholas Yong

The response to Menon’s final wish has greatly comforted his family, said Jayanthi. “It filled me with this very strange sense of happiness, to think that he’s inspired people even upon his death. His thinking was ‘I’m gone, but at least my body can be put to good use’”

Asked why he had made the decision all those years ago, his widow Sathi Devi, 77, admitted, “I don’t really know where he got the idea from. That is a question we should have asked him long ago.”

Devi, who was married to Menon for 57 years, added with tears in her eyes, “Many people, when they heard it, said ‘Oh, he’s a great man, he’s a great man.’”

Both mother and daughter are following in Menon’s footsteps - Jayanthi pledged her body to science last year.

Devi, 77, also wants to get an organ donor card - provided “I have got anything left in my body”, she said with a laugh.

To find out more about pledging your body for medical research, contact the National Organ Transplant Unit at 63214390 or organ.transplant@notu.com.sg.