Flowered Up captured the spirit of rave and baggy – but they were always headed for tragedy

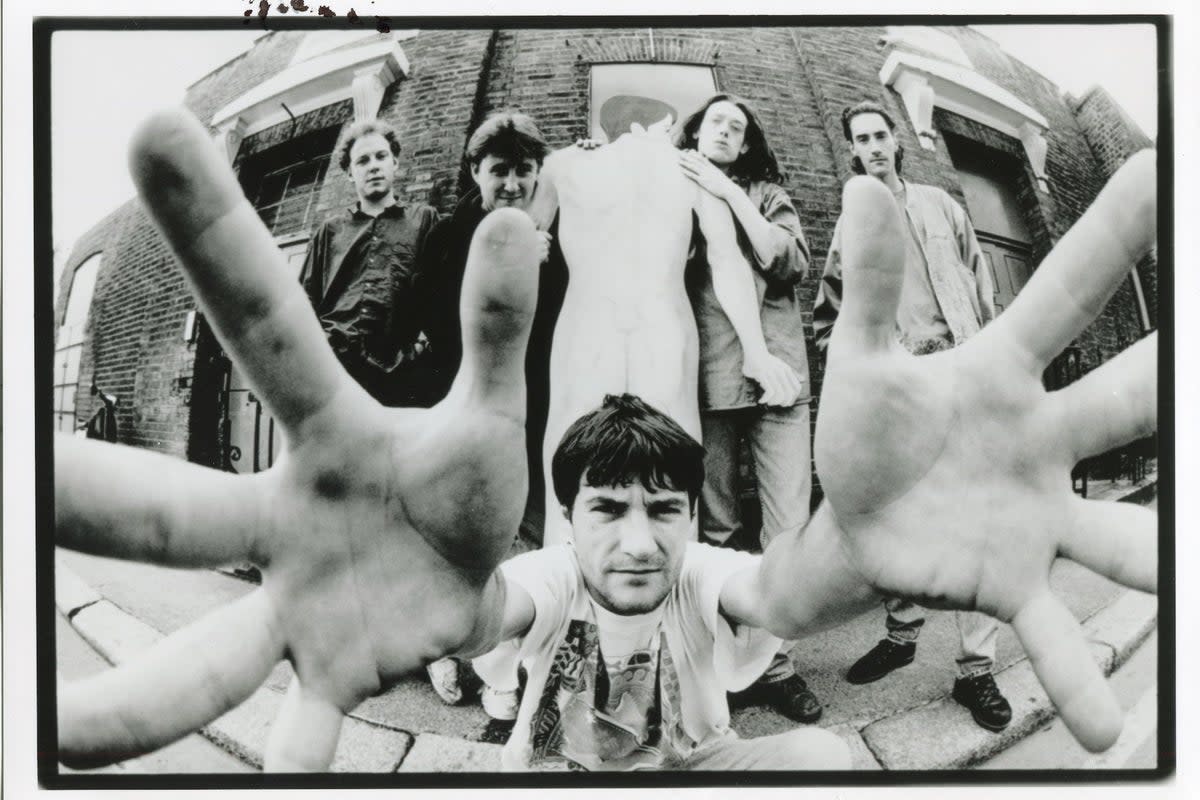

They were the “southern Happy Mondays”: a gang of north London scruffbags who burst out of late-Eighties British clubland, perfectly formed to fit with the then-dominant culture, at the sweet spot where acid house met baggy. A band of estate-kid mates with a pair of battling brothers at their heart. They looked, according to one music industry figure, amazing: the singer “had the face [and] the wardrobe of the times”. But that label boss didn’t want to hear any music – “it’d be terrible if it was rubbish”. And this was the man who signed them. They were, according to a contemporary interview in the Melody Maker of 18 April 1992, “at best rogues, at worst out-and-out thugs”.

They were Flowered Up and they bloomed brightly, brilliantly and briefly – a pair of luminous singles, a brace of calamitously thrilling gigs, a so-so album and a final testament that reverberates to this day: a 13-minute single and accompanying 18-minute video, Weekender. “Epochal” doesn’t do it justice.

Weekender was “really the first proper meditation, in a way, on the rave scene”, according to Jeremy Deller, the Turner Prize-winning artist and thoughtful chronicler of those times, reflecting on a film that was restored and re-released last year by the British Film Institute. “The first artwork produced about the rave scene.” Or, as the band’s contemporary Shaun Ryder puts it: “I would describe it as a mini-masterpiece movie.”

“Some films are a voice for people,” says singer Róisín Murphy, her thoughts recorded for last year’s making-of documentary, I Am Weekender. “You see yourself in it and you’re given a voice… [If] that happens to you… it never leaves you. It also remains something very important to you.”

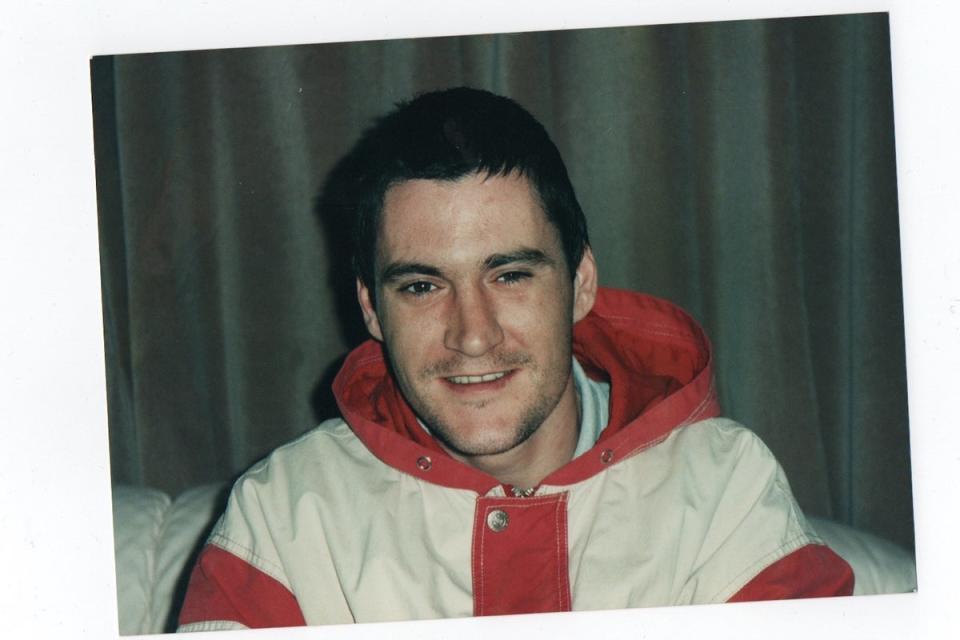

Flowered Up, though, couldn’t keep up with all that. The things that helped make them a thrilling, disruptive musical force were also the things that killed them. By the time of the release of the first single from their second album, they’d split, the drugs and attendant chaos sending most of the members spiralling. Then the singer, Liam Maher, died of a heroin overdose. Three years later his guitarist brother Joe, who’d similarly struggled for years with addiction, also died.

“I wasn’t particularly surprised,” Flowered Up keyboard player Tim Dorney replies when I ask how he felt when he heard about the 2009 death of the charismatic Liam, he of the face and the wardrobe (not to mention the de rigueur Caesar haircut). “But it hurt because I loved the guy. Out of all of them, he was my brother in it. He was a very charismatic and a very kind, loving man. I was gutted when he went, I really was.”

But in the opinion of Jeff Barrett, the Heavenly Recordings founder who first signed the band and released two singles with them before handing them over to London Records in a £250,000 album deal, “it was only ever going to end in tears”. At least now, though, 31 years after their messy dissolution, Flowered Up are having another moment in the sun.

This month London Records are reissuing, on vinyl for the first time, their sole album, 1991’s A Life with Brian. Also for the first time: it’s being packaged with Weekender, the non-album single that came out the following year. There are, too, new remixes from Beyond The Wizards Sleeve and Everyone You Know, the latter the young Greater London duo who Dorney believes are “carrying on what we sort of were. I really like [singer/rapper] Rhys [Kirkby-Cox’s] vocal delivery. They’re a great band”.

As a whole, the double-disc release package – completed by album remastering overseen by Dorney – is a thrilling evocation of a band of the moment who, probably fundamentally, were fated to never live beyond that moment. As the keyboard player says of the new version of the album, “we made it louder, wider and punchier all round” – which also happen to be three clangingly apposite adjectives for Flowered Up.

“It was a wild time,” reflects Barrett. “Even thinking about it now, I have to pinch myself that it really did happen.”

Des Penney, former Flowered Up manager and sometime co-lyricist with Liam, knew the Mahers from their respective childhoods on the post-war Regent’s Park Estate in Camden. His telling of the band’s origin story goes like this: “The night I proposed to Liam that he sang with his brother Joe and his two mates, the rhythm section,” he says of Andrew Jackson and John O’Brien, “was the night The [Stone] Roses played Dingwalls for their album launch. Although my chronological memory is a bit shot, as you can imagine.”

History tells us that The Stone Roses released their self-titled album on 2 May 1989, and that they played Dingwalls in Camden Lock on 22 May.

Dorney joined the following March. “They only had four songs at the time,” says the 59-year-old, when we meet in central London. (Dorney would later form Nineties indie-rave crossover band Republica.) “I’d been doing stuff with Andy Weatherall, helping out at the studio. He heard that they were looking for another keyboard player and gave them my number.”

His first impressions?

“F***ing lunatics!” he says, laughing. “I was dead nervous. I didn’t know the songs, I was just trying to work out keyboard bits that went along with the songs they had. I don’t think there was a fight at that first rehearsal. But then the second one turned into a full-on fist fight between Joe and Liam because Joe had looked at Liam the wrong way or something. It was eye-opening for a middle-class bloke from Windsor.”

They were, he agrees, classic battling brothers, their sibling rivalry animating the band in exactly the same way it would another powder-keg combo who came along four years later.

“It was very much an Oasis thing,” says Penney of what made Flowered Up special. He’s referring to the idea of a band appearing at the right time, right place. But it applies to the family dynamic, too. “It was one of those moments where, if we hadn’t have filled it, someone else would have. They were superb musically,” he adds, of a band powered by the supremely talented Joe’s limber, funky, propulsive guitar – not quite John Squire level but getting there. “They really could play. It was fresh, it was fun, it was completely authentic. And it was a way for us to carry on the acid house [vibe] when most of [that scene] was falling apart around us.”

I’d go to the gigs but they were too naughty for me, to be honest. They’d get up to real bad mischief, and not just the drugs. Criminal stuff went with the territory to a degree

Jeff Barrett, the Heavenly Recordings founder who first signed the band

Having caused a noise on the London club and gig scene, Flowered Up were signed by Heavenly. Such was the hype, and such was the music industry’s gold-rush mania to find the next baggy outfit after Happy Mondays, The Stone Roses and The Charlatans, the band had three weekly music press covers before releasing a note of music.

“It was a bit of a rollercoaster,” remembers Heavenly’s Martin Kelly with some understatement. “Whereas the Mondays had been a band anyway and gone through the club scene, Flowered Up might have been the first band to fully emerge from the club scene. They were just kids that were going out clubbing in London seven nights a week.” The Mahers’ volatility, he adds, was “100 per cent” part of the magic in the early days. “They were street kids, and they wore that attitude on their sleeves.”

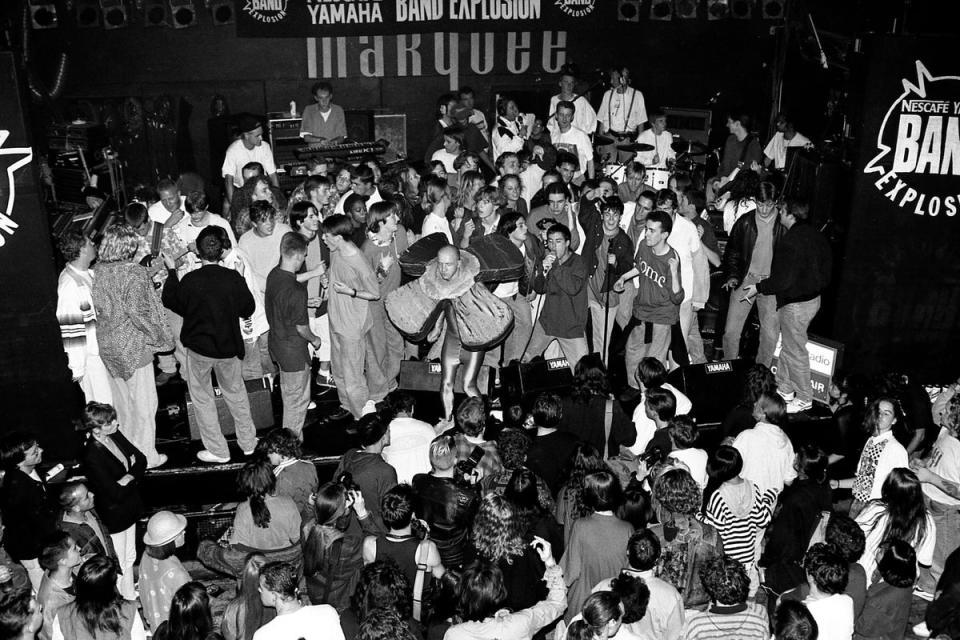

I saw Flowered Up at Edinburgh’s The Venue, which history – aka the internet – tells me would have been November 1990. All I remember is a tiny, low-ceilinged room packed to the actual sweating rafters, and a gang of musicians comprising mostly, it seemed, limbs flailing about on stage, backed by a man dressed as a giant flower. This was Barry Mooncult, ex-Chelsea Headhunter football hooligan and now the band’s own Bez, a dancing mascot. It was mayhem.

“That period was so great,” Barrett said to me in 2020 when I interviewed him about Robin Turner’s book Believe in Magic – Heavenly Recordings: The First 30 Years. “When I saw them at Glasgow Mayfair [now The Garage], the stage caved in because too many people were on it. I saw Liam’s head poking out [the floor], him carrying on singing – it was hilarious! They were having such a brilliant time I couldn’t believe there was anything behind the scenes that was going to stop it.”

He’s referring to the band’s extracurricular habits. “I’d go to the gigs but they were too naughty for me, to be honest. They’d get up to real bad mischief, and not just the drugs. Criminal stuff went with the territory to a degree.” But something else going on behind the scenes didn’t help, either. After Flowered Up’s pair of 1990 Heavenly singles, “It’s On” and “Phobia”, London Records swooped, signing the band for a hefty advance.

Then it occurred to me: someone wanted to use the foil Kit Kats were wrapped in at that time. That was the first time I realised they’d got into smack

Martin Kelly

“We didn’t know what we were doing,” admits Dorney of the band’s attempts to record an album. “We were thrown into Eel Pie in Richmond, which was Pete Townshend’s studio. With hindsight, we were a live band. We should have been chucked in a room, everything mic’d up, and it should have been recorded and mixed in three weeks, not three-and-a-half months. It shouldn’t have been produced to the nth degree. That’s where we went wrong. We were bedazzled by the flashing lights.”

On top of that, according to Barrett, “their manager didn’t understand that that quarter-of-a-million included recording costs. Which of course they’d spent by the time they left Eel Pie after several abortive attempts at making a decent record. They’d accepted they’d never make a decent f***ing record, and then someone said, ‘Here’s your bill’.”

Meanwhile, habits were getting out of hand. For the Mahers, the ecstasy and cocaine that were, frankly, part and parcel of music and club culture at the time had been supplanted by something much darker.

“I remember being in the Heavenly office on Monmouth Street [in Covent Garden],” says Kelly. “In the toilet I saw a Kit Kat out of its wrapper. I’m thinking: who would unwrap a Kit Kat and leave it? Then it occurred to me: someone wanted to use the foil Kit Kats were wrapped in at that time. That was the first time I realised they’d got into smack.”

Nonetheless, the addicts and ne’er-do-wells of Flowered Up still managed to deliver their towering achievement. Weekender was recorded as part of their deal with London. But when the major label baulked at releasing a 13-minute single and suggested two “solutions” – a three-and-a-half-minute edit, or a 500-copy, fan-only 12-inch – the band high-tailed it back to Heavenly. Barrett and Kelly, by now in a label partnership with Sony, were only too happy to have them back. And not only did that second major label agree to release the full version, but they also ponied up the budget – £30,000 – for an ambitious short film to accompany Weekender.

“Within two minutes, I got a sense that this was something majestic,” remembers Weekender director Andrew “Wiz” Whiston of the first time he heard the song. “As the track unfolded, with all its tempo changes, it was this wonderful, cinematic, sonic narrative. It pressed all these buttons I’d had about this need to make a film about what was exploding all around us [in culture].”

The filmmaker’s aim was as ambitious as the band’s: he wanted to tap into the “revolutionary spirit that was emanating through the country. It was being expressed most nights of the week, but certainly at the weekends, in a most exuberant, loud and shameless way on the nation’s dancefloors.”

The original plan was for Liam Maher to take the lead role of a young nine-to-fiver going out clubbing and (to quote the lyrics) having a good, good time. “Whatever you do,” ran the tagline, “just make sure what you’re doing makes you happy.”

“Liam was very excited about that, and everyone could see that this was going to be special,” says Wiz. But unfortunately, that was already beyond him. “It wasn’t a one-day music video, it was an intense seven-day shoot, a tight schedule, very early starts. And as we got closer to production, he understood that he probably would let us down because of his addiction.

“Eventually he said, ‘Listen, Wiz, man: I’m so gutted, I’m not going to be able to do this’. It was heartbreaking but it was a silver lining – Lee Whitlock, an experienced actor, a professional, was cast. Whereas if we’d done it with Liam, we’d still be shooting now!”

There was, though, another brutal blow down the line. Whitlock – who went on to have a busy career in multiple TV dramas including The Bill, Grange Hill, EastEnders and London’s Burning – died last February, aged 54, days before completion of I Am Weekender.

The long-tail success of Weekender came way too late for Flowered Up. In early 1993, Dorney quit the band, patience finally broken, with Liam following suit two days later.

Joe overdosed on something, and I ended up spending the rest of the evening in hospital with him having his stomach pumped. And I was like, ‘No, I’m not doing this again. Bye!’

Tim Dorney on the Flowered Up 2005 reunion

But even in Flowered Up’s afterlife, the dysfunctionality and mayhem continued. Tim Dorney and Liam Maher pair reunited in 2001 under the name Greedy Souls, signed to Alan McGee’s Poptones label. But a great album (Dorney sent me a copy) went unreleased when, according to Dorney, a member of Flowered Up’s old entourage beat up a Poptones employee, “so we were unceremoniously dumped”.

Then there was a Flowered Up reunion for 2005’s Get Loaded in the Park on Clapham Common, a baggy throwback festival also featuring Happy Mondays and The Farm. “Joe was living in hostels and under stairs at that point. Liam was all right but not great,” remembers Dorney. At the event, “Joe overdosed on something, and I ended up spending the rest of the evening in hospital with him having his stomach pumped. And I was like, ‘No, I’m not doing this again. Bye!’”

Four years later, Liam died, aged 41. Three years later, Joe, one year younger than his brother, followed suit.

Flowered Up’s legacy, though, incarnated by Weekender, the epic song and the epic film, remains vibrant and alive. Shaun Ryder’s beloved “mini-masterpiece movie” – certificate 18 and banned at the time by the BBC and ITV for its depiction of what young people really got up to at the weekend – feels as powerful and as relevant now as it ever did. And that’s an actual legacy, too: Dorney explains that, with the A Life With Brian re-release, “we’ve made sure that the descendants of Liam and Joe are looked after – the deal is split with them receiving Joe and Liam’s [share]. We weren’t going to cut anybody out.”

As for what this cult, all-too-brief band mean now, Des Penney circles back to “everything Weekender encompasses: even when you’re down and out, if you’ve got the spirit, the quality, you’ve got a chance. The other unfortunate side is that, unless you take control of negative controlling spirits, they will take control of you.”

‘A Life with Brian’ (London Records) is released on 19 April