GE2020: A primer for first-time voters from role of MPs to GRCs

By Christalle Tay

SINGAPORE — After months of top government leaders hinting at an election during the COVID-19 pandemic and the opposition pushing for one to be held after the crisis, President Halimah Yacob on Tuesday (23 June) ended the speculation by dissolving Parliament on the advice of Prime Minister (PM) Lee Hsien Loong.

The dissolution of Parliament – a key step towards holding the next General Election (GE) – might be an unfamiliar proceeding for younger Singaporeans. If you turned 21 before 1 March this year and are therefore eligible to vote, you might want to read this article to avoid being bewildered by election lingo and acronyms during this GE season.

Those whose 21st birthday falls after the 1 March deadline will have to wait for the next GE to cast their vote.

Candidates who are contesting will reveal themselves and their targeted constituencies on Nomination Day next Tuesday (June 30). In recent days, the ruling People’s Action Party and several opposition parties have been unveiling their candidates as soon as the 10 July Polling Day was set. Once nomination closes, the nation will turn its attention to the socially-distant campaigning, deliberate its choices on Cooling-off Day (9 July), when election chatter will be forbidden, and give its mandate at the polling stations the next day.

These dates were given in the Writ of Election, a document issued in tandem with Parliament’s dissolution.

There are three types of Members of Parliament (MP), two of which will be decided by the GE. They are the elected MPs, candidates who won the majority of the votes, and the non-constituency MPs (NCMPs), colloquially known as the “best losers” as they are seats offered to defeated opposition politicians with the largest percentage of votes.

There can be up to 12 NCMPs, though the exact number depends on how many opposition politicians get into Parliament. If none succeed, all 12 seats will be open, to ensure opposition representation in Parliament. But if the opposition were to win six seats, like the Workers’ Party (WP) did in GE2015, six NCMP seats would be up for grabs.

Not all opposition politicians are eager to take up NCMP seats, however. WP candidate for Punggol East in GE2015, Lee Li Lian, rejected the seat, paving the way for the next “best loser” and her fellow party member Daniel Goh to take up the position. The seats were also turned down in 1984 by the opposition politicians they were offered to, the first GE that the scheme was introduced.

Five opposition leaders, including then WP chief Low Thia Kiang, said in GE2011 they would reject the seats if offered.

The reluctance may be from the limited responsibilities of an NCMP, who unlike an elected MP, does not run a town council or have residents to answer to. Most importantly, before the rule changes in 2017, NCMPs could not vote on affairs relating to the Constitution and public money, among other things.

Parliament requires a two-thirds majority to pass bills into law and amend the Constitution, which is easily obtained by the PAP, whose members are compelled by the Party Whip to vote with the party. The Whip is occasionally lifted to “allow MPs to vote according to their conscience”, according to the Singapore’s Parliamentary website. It was last lifted during a parliamentary debate in July 2017, about the dispute between PM Lee and his siblings over their father Lee Kuan Yew’s Oxley Road property. However, no vote was taken after the debate.

Losing opposition politicians may be more enthused to take up the role after this GE, following amendments to the scheme in 2017 to give NCMPs equal rights as elected MPs and raise the ceiling on the number of NCMPs from nine to 12.

The third group of MPs — up to nine nominated MPs (NMP) — are apolitical and appointed by the President. The NMPs, usually distinguished members of their fields, serve for two and a half years and have limited voting rights.

Why should I care about my MP?

Election winners, or elected MPs, represent voters’ interest in Parliament on national and municipal levels. Parliament is the platform for MPs to air their concerns and they have covered topics such as offences for feeding pigeons, cats in HDBs and high-rise littering. One memorable exchange took place when Nee Soon MP Lee Bee Wah cited an example of a persistent litterbug who would throw her sanitary pads from her flat.

But the duties of MPs are not restricted to just parliamentary work. Electoral divisions, also known as constituencies, are usually merged to form town councils, which are managed by MPs. Town councils run the common areas of HDB flats and commercial property within the town.

Since their inception, town councils are dubbed a “training ground” for MPs, who make municipal decisions affecting their constituents’ lives.

“If your MP is not honest, or not competent, you will know it soon enough,” said then PM Lee Kuan Yew in 1988. “And if your estate is poorly run, repairs slow, and lift maintenance poor, you will be inconvenienced and worse, the resale value of your flat will be affected...Your personal well-being will be at stake when you choose your MP.”

Based on arguments in previous election campaigns, town councils are seen as a metric of a political party’s competency. Well-run town councils showcase the politicians’ ability at governing — and by proxy, the ability to run a country — while town council scandals are used to take down political opponents.

Although towns are managed differently by each group of MPs, changes to service and conservancy charges (S&CC) – maintenance fees for HDB flats and commercial properties – are passed across town councils under the same party banner.

A 15 per cent rebate on S&CC for commercial properties in PAP-run towns from July to October was announced early this month. Almost two weeks later, the Aljunied-Hougang Town Council announced a 25 per cent rebate for its commercial properties, from June to August.

In the early 2000s, residents in PAP constituencies had refurbished lifts, while those in opposition wards were stuck with older lifts that stopped at every few floors. Lift upgrading was a hot-button election issue and a carrot dangled by PAP MPs to constituencies in past elections.

Shortly before GE2001, then National Development Minister Mah Bow Tan said, “It's only fair that we give those constituencies that have given us support, higher priority." Three days before GE2006, then Senior Minister Goh Chok Tong promised Hougang residents a $100 million upgrading plan, should the PAP win.

This changed in the last decade when the opposition wards of Hougang and Potong Pasir were selected for the lift upgrading programme in 2009. By the end of 2014, the programme was completed for all eligible flats, and most flats were refurbished with lifts that stopped on every floor.

Those in private residences may rely on their MPs less, but they come in handy in tussles with bureaucracy. Or even in matters such as cleanliness in a neighbourhood or if residents want to express their unhappiness over a policy. MPs often handle these issues during their weekly Meet-the-People sessions, which have gone online since April because of the pandemic.

What are SMCs and GRCs?

Singapore is cut up into constituencies where Singaporeans cast their votes for the contesting candidates during a GE. The two types of constituencies are better known by their acronyms: single member constituencies (SMCs) and group representation constituencies (GRCs).

The constituencies are laid out in a report by the Electoral Boundaries Review Committee (EBRC), which redraws the boundaries shortly before every GE. The report is always highly anticipated as it signals an election is around the corner. The dissolution of Parliament happened about three months after the EBRC report was released on 13 March.

SMCs, or single-seat wards, are where candidates run as individuals. In previous GRCs, candidates ran as groups of three to six, depending on the constituency. Each GRC team must include a candidate who is a Malay and an Indian/Other.

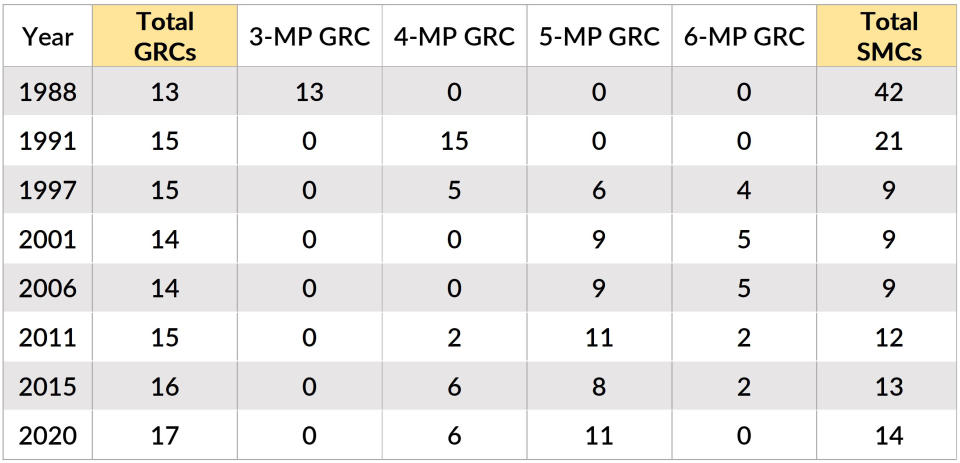

A number of SMCs were merged to make way for the GRC scheme introduced in 1988. The scheme, said to ensure ethnic representation in Parliament, initially mandated that candidates contest in a trio with at least one ethnic minority.

Over time, the scheme was expanded to allow up to six members in a GRC. The government had justified the change by arguing that larger GRCs could reap economies of scale and save money by managing larger town areas.

A number of opposition parties have long objected to the scheme because they struggle to field enough candidates in GRCs.

These parties also argue that the scheme is designed to bring less experienced PAP candidates into Parliament. Phrases like “riding in on ministers’ coat-tails” and “anchor minister” were bandied around, referring to how top ministers led larger GRCs. Singaporeans would be cautious in voting against PAP-led GRCs over fears of dislodging ministers during an election, according to the opposition.

However, such fears appeared to be unfounded during GE2011. Then Foreign Minister George Yeo, and Second Minister for Finance and Transport Ms Lim Hwee Hwa and Senior Minister of State for Foreign Affairs Zainul Abidin Rasheed were ousted following WP’s historic win in Aljunied GRC.

SMCs, on the other hand, have a lower entry barrier as political parties need to field only one candidate of any race in each ward. They are easier for smaller opposition parties with fewer resources or manpower, and sometimes attract independent candidates.

The number of SMCs has been increasing in recent years. This followed PM Lee’s promise in 2009 to reduce the size of GRCs and increase SMCs to at least 12, which was fulfilled in GE2011.

By GE2015, the number of SMCs rose to 13. In comparison, the average size of GRCs shrank from 5.4 in 2006 to 4.8 in 2015.

PM Lee followed up with another promise in 2016 to further shrink GRCs and increase SMCs, prompting eager participation for this year’s EBRC report. The EBRC added one SMC and trimmed the two jumbo six-member GRCs – Pasir Ris-Punggol and Ang Mo Kio – to five-member GRCs.

Political parties for the coming election had three months – the most time they have had over the last five GEs – to ponder over the new boundaries.

Despite the opposition parties objecting to the GE being held amid the pandemic, they appear to have pressed ahead with their campaign including unveiling new candidates and highlighting key issues of concern to voters.

GE2020 is “like no other”, as PM Lee put it, and looks set to be the most closely watched ever.

Follow Yahoo News Singapore’s GE2020 coverage here.

Stay in the know on-the-go: Join Yahoo Singapore's Telegram channel at http://t.me/YahooSingapore

Related stories:

GE2020: Workers' Party unveils 5 more candidates including ex-NCMP Dennis Tan

Ivan Lim saga: PAP’s Masagos says GE is time for candidates to ‘redeem’ themselves