‘The pain hasn’t gone away’: Women of Xinjiang reveal horror of China’s brutal campaign of forced abortions and imprisonment

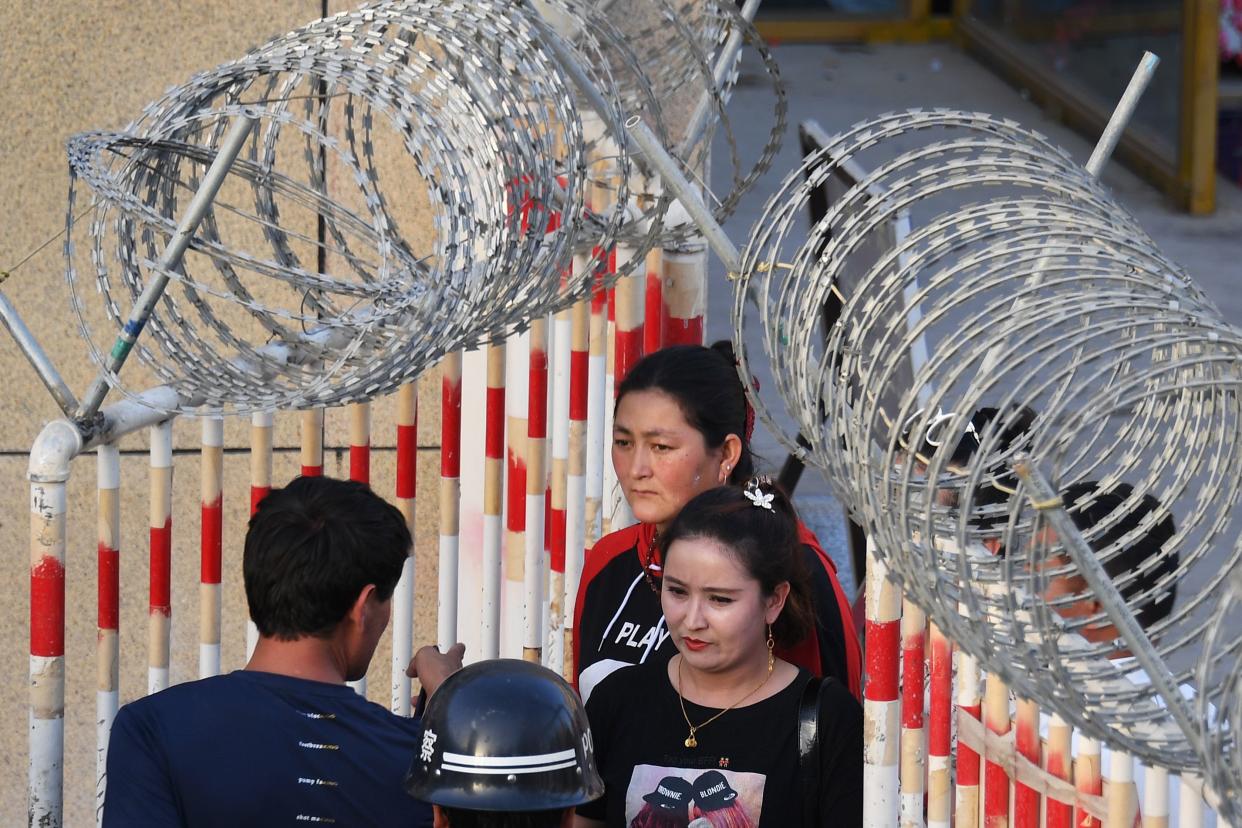

Around midnight on 25 December 2017, police came to the house of Gulziya Mogdin in the western Chinese region of Xinjiang. They drove her to the hospital. Mogdin knew a medical checkup was the first step in a process through which ethnic minorities such as herself, a Kazakh, were being placed in political indoctrination camps by the Chinese government. Mogdin, 39, had moved to Kazakhstan to live with her husband, a Kazakh citizen. But earlier in the year, Chinese police had demanded that she cross the border back into China together with her two children from a previous marriage.

Five days before the police visit, Mogdin had found out she was pregnant. Her pregnancy also showed up during the medical examination. The next day, she says, authorities started pressuring her to get an abortion. She resisted, saying she couldn’t end the pregnancy without her husband’s consent. The following month, Mogdin was summoned to the local administration office. An official told her that if she refused an abortion, her brother would be held accountable. Fearing her brother could be locked up because of her, she relented. She had the abortion on January 5th.

Mogdin is among thousands of Xinjiang women who are being targeted in China’s campaign to assimilate ethnic minorities through methods such as mass internment, family separations, curbs on language and religion, forced labour and alleged forced abortions and sterilizations. Families are being forced apart, with government documents appearing to show thousands of Uighur children left without parents, according to leading Xinjiang researcher Adrian Zenz.

Xinjiang, a resource-rich region the size of Iran, is home to about 11 million Uighurs, a Turkic-speaking minority, as well as Kazakhs, Huis, Tatars and other predominantly Muslim minorities. The Chinese government started the multifaceted campaign in 2016, after ethnic clashes and sporadic attacks blamed on Uighurs had rocked the region in previous years. Beijing says the policies are needed to curb terrorism, separatism and religious extremism. But internment camp survivors, rights groups and foreign governments say people are being swept up arbitrarily for reasons such as praying, travelling abroad or having banned apps such as WhatsApp on their phones. Experts estimate more than 1 million members of ethnic minorities have been put in internment camps since the campaign began.

Thirty-nine countries including Britain, the United States and Germany last week condemned China for its Xinjiang policies. The move drew a swift pushback from Beijing, which accused the nations of spreading “false information and political virus” and interfering in China’s internal affairs.

As the Xinjiang campaign gains more international awareness, women’s plight has also come front and center. Women, along with their husbands, brothers, fathers and sons, are being locked up inside internment camps, where survivors have reported beatings, abuse, forced medication and sterilizations. Additionally, the government has cranked up policies meant to slash birth rates across the region, with local governments encouraged to implant intrauterine devices (IUDs) and conduct sterilizations on a massive scale, according to a report published in June by Mr Zenz. In 2018, 80 percent of all net added IUDs implanted in China occurred in Xinjiang, though the region makes up only 1.8 percent of the nation’s population. As a result, birth rates in Xinjiang plummeted 24 percent last year compared to 4.2 percent nationwide, according to official statistics.

But at the same time, Xinjiang women are increasingly rising up against Beijing. Mogdin is among several Kazakh and Uighur women who after escaping China, have spoken out about their ordeals in an attempt to hold the country accountable.

“I can say that the pain of the loss is still there; it hasn’t gone away yet,” Mogdin tells The Independent. She returned to her home in eastern Kazakhstan in May 2018, after four months of home detainment during which her husband, Aman Ansagan, appealed to the Kazakh government, the Chinese embassy, NGOs and journalists, trying to secure her release. The couple hasn’t been able to get pregnant again. They are seeking to sue China for the alleged forced abortion.

For Zumret Dawut, a businesswoman from Xinjiang’s capital of Urumqi, a nightmarish couple of months started, just like for Mogdin, with a hospital visit. Dawut says she was called into the local police station in late March 2018. Police asked about her travels, phone calls and bank transfers related to an import-export business she was running with her Pakistani husband. They held her overnight.

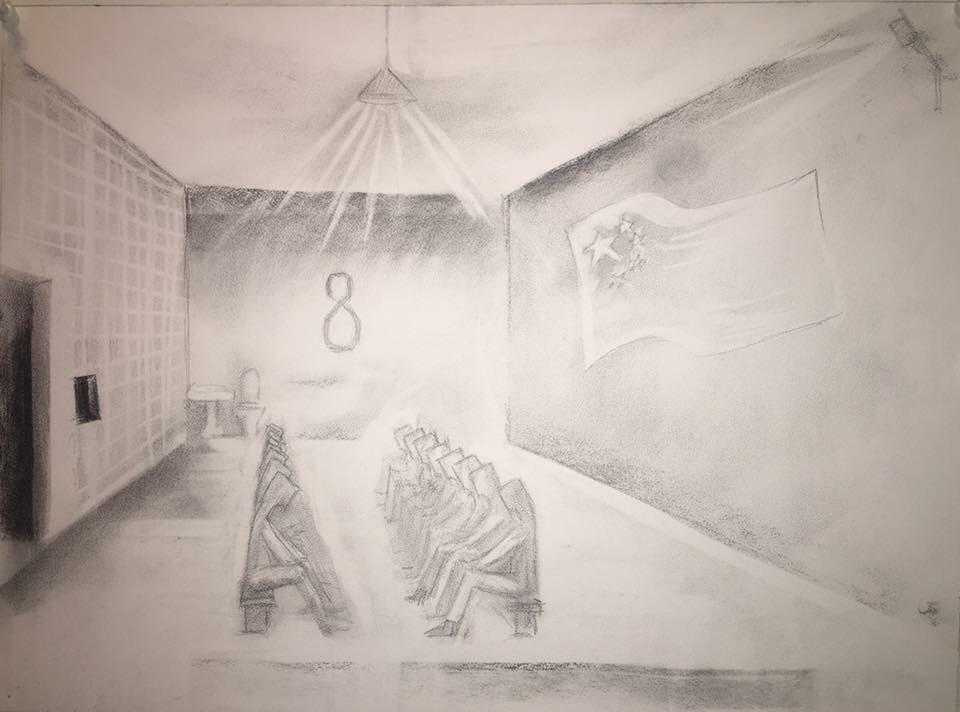

The next morning, they drove her to a local hospital where Dawut says several Uighur women were lined up accompanied by police. The hospital collected her biometric data, including voice recordings, blood samples, iris and X-ray scans. Next, she was driven to one of Xinjiang’s political indoctrination camps, which the Chinese government calls “vocational education centers”.

Inside the camp, Dawut tells The Independent she shared a cramped cell with 27 other women. Every day, they would be taken to a “classroom”, where they would study Mandarin Chinese and President Xi Jinping’s ideology while sitting on the cold concrete floor. “Every day when we left the room we were asked: ‘Is there Allah?’” Dawut says. “On the first day, I didn’t want to say no. [The guard] used a plastic baton to hit me and asked, ‘Why won't you answer?’ I was afraid of being beaten, so I said, ‘No, there isn't.’ Allah stayed in my heart.”

One night during dinner, Dawut shared her bread ration with an elder prisoner who was suffering from diabetes. The next night, she did the same. Suddenly, out of nowhere, two guards came and started beating her. She cried, “Allah!” To which one of the guards said, “If your Allah is so great, call him, and let him save you.” Dawut says she was forcefully given unknown medicine, which had a tranquilizing effect. She says women in her camp were divided into three categories, according to their perceived offence: being religious; having a travel history or relatives abroad; or having banned apps such as Facebook or WhatsApp on their phones. Of these, being religious was considered the most serious offense.

Dawut was released after her Pakistani husband appealed repeatedly to his embassy and to the public security bureau in Urumqi and threatened to speak to foreign journalists. The couple and their three children left the country and ultimately settled down in Virginia, in the US. But before she could leave Xinjiang, Dawut says she was fined for having a third child and forced to undergo sterilization.

While Mogdin and Dawut’s stories cannot be independently verified, it is in line with the testimonies of other people who escaped Xinjiang. The region itself is tightly controlled, and state security officials prevent foreign journalists from speaking to locals. Dawut testified last September during the United Nations General Assembly in New York because, she says, she wanted to help other Xinjiang women in her situation.

The women who speak out illustrate courage and hope for the Xinjiang cause, says Zubayra Shamseden, Chinese outreach coordinator at the Uyghur Human Rights Project (UHRP). “The Chinese government wants to re-engineer the Uighur woman in order to completely conquer the Uighur nation, but it’s impossible [due to] the testimony of camp survivors,” Shamseden says. “Those women are so brave, so hopeful. They are living with dignity still.”

Sophia, a woman from Xinjiang who did not want her real name revealed because her residence documents abroad are still pending, spent six and a half months inside an internment camp in her hometown because she had travelled to Kazakhstan. She describes a daily schedule of intimidation, boredom and beatings.

Sophia showed The Independent medical documents saying she had swollen internal organs as a result of physical trauma. She also showed a receipt of 1,800 yuan (roughly 200 pounds) for the food she consumed inside the camp and for which she was forced to pay. Sophia says recounting her experience is traumatizing, but she does it in the hope that it will prevent others from sharing the same fate.

“I can’t even say I hate [my oppressors] because I lived with them for a while,” she says. “I just hope it ends and nobody else will suffer.”

Dinara Saliyeva contributed reporting.

Read more

China denies forced sterilisation as Xinjiang birth rates plummet

What life is really like inside China’s orphanages for Uighur children