Rap music and anti-Semitism: how Wiley’s tweets draw on a long and ugly history

Grime artist Wiley has been dropped by his management and banned from Twitter for an extraordinary tirade of anti-Semitic posts late last week. In the heavily criticised flurry of Tweets, Wiley, real name Richard Cowie, likened Jews to the Ku Klux Klan and told them that Israel is not their country. Twitter’s perceived lateness in removing Wiley’s broadside prompted further outrage, and has led to condemnation from the Home Secretary and the Prime Minister, as well as a 48-hour boycott of the social-media platform by thousands of disgusted users.

The grime artist’s outburst is just the latest in an unfortunate line of anti-Semitic controversies emanating from certain members of the hip-hop community. Some rappers have an uncomfortable track record of anti-Jewish sentiment that goes back decades – leading to a 2011 Jewish Chronicle article calling hip hop “the music where it’s okay to be anti-Jewish”. But where does the animosity stem from? And what can be done about it?

There are, unfortunately, dozens of examples of anti-Semitic sentiment in rap. In 1988, Public Enemy’s Professor Griff made a series of anti-Semitic and homophobic comments to Britain’s Melody Maker magazine, including: “If the Palestinians took up arms, went into Israel and killed all the Jews, it’d be alright.” The following year, he continued his attack in The Washington Times, telling the paper that Jews were “responsible for the majority of wickedness in the world”. He was removed from the band soon afterwards.

Ice Cube, meanwhile, has long made references to Jews in his raps. His 1991 track No Vaseline contains a line about his former band NWA “letting a white Jew tell you what to do”, in reference to the collective’s manager Jerry Heller. Only this month, the rapper was criticised by NBA basketball star Kareem Abdul-Jabbar in The Hollywood Reporter for anti-Semitic Tweets. Ice Cube had posted a picture of the controversial Freedom For Humanity mural depicting businessmen – assumed to be Jewish – playing a board game that rests on the back of hunched, naked figures. He was one of several black celebrities criticised by Abdul-Jabbar, and responded on Twitter that The Hollywood Reporter had given the sportsman “30 pieces of silver” for his opinion.

Elsewhere, seven years ago, rapper Scarface said the music industry was “so f-cking white and so f-cking Jewish", and although hip-hop royalty Jay-Z has stood against anti-Semitism and equated it to racism, his 2017 track The Story of OJ contained the lyric: “You wanna know what’s more important than throwin’ away money at a strip club? Credit/ You ever wonder why Jewish people own all the property in America? This how they did it.” Similar sentiments have appeared in the work of Mos Def and Lupe Fiasco.

And earlier this month, celebrity TV host and rapper Nick Cannon was dropped by Viacom CBS for making anti-Semitic statements, prompting more furious anti-Jewish comments by rapper Jay Electronica in defence of Cannon. Do you see a pattern here?

The truth is that Wiley’s latest salvo is nothing new. In 2010, Professor Glenn Altschuler, a professor at Cornell University in New York, gave a lecture in which he said that some rappers helped give anti-Semitism “authority and credibility” in the 1990s. But the problem goes back much further, to the very roots of hip hop.

Beyond demonstrating its participants’ ability to rhyme and entertain, the whole point of rap when it emerged in the 1970s was to articulate, through music, the experience of growing up black in America. The genre quickly found an audience “eager to deride, degrade and disrespect authority, tradition and race-based hierarchies”, Altschuler said. Many black communities had developed in areas with a large number of Jewish shopkeepers and landlords, and it was this latter group that provided some of the perceived authority and tradition against which musicians could rail.

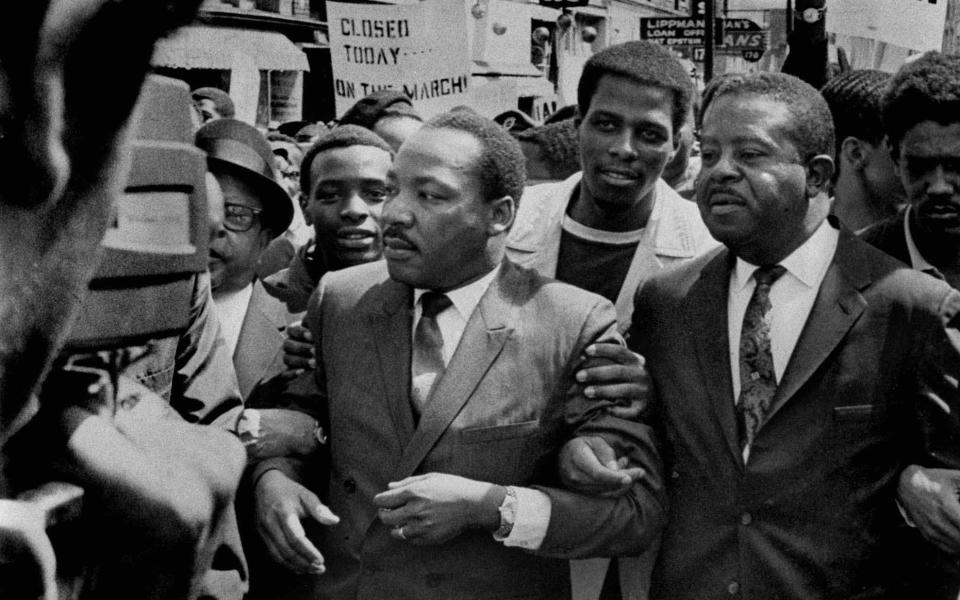

Animosity between black and Jewish communities can be traced back even further than the dawn of rap: civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr, who died in 1968, once described how Jewish landlords in Chicago charged more rent to black tenants than white tenants. So when the empowerment and expression of rap music started to become politically charged as the genre took off, anti-Semitism crept into some lyrics.

“Rappers revised, rewrote and recycled ‘history’, shining a demonic light on race, racism and the exploitation of black people by Jews,” Altschuler said in 2010. He added though that the rise of the Gangsta Rap sub-genre, also in the 1990s, started to shift focus from racism to street life, violence and money, moving things on from anti-Semitism. But it appears the pendulum has swung back.

The large number of prominent Jewish people in the upper echelons of the music industry is another commonly held reason for rappers’ annoyance. But this argument makes little sense. These executives got to the top because they love music and seek to champion its stars. Take the story of Lyor Cohen, the son of Israeli immigrants who became Run-DMC’s road manager in the early 1980s when he was a gangly young music-industry rookie. Cohen was attacked by Mos Def (“some tall Israeli is runnin’ this rap shit”), yet he became many a rapper’s trusted colleague and friend. He went on to run the Def Jam record label (co-founded by Rick Rubin) before becoming boss of Warner Music Group, and he is now head of music at YouTube. It’s only one example, but Cohen’s steady rise up the ladder puts paid to the idea that the music industry is a top-down conspiracy of industry execs at one end and struggling artists at the other.

One line of argument goes that many rappers are simply angry at anything different to themselves, Jewish people being just one target. Making a general point regarding anger in an essay about rapper Eminem in 2001, writer Nick Kent said it almost doesn’t matter who or what American musicians (and filmmakers) are kicking against. “Blind rage alone will suffice,” he wrote. When Eminem rapped “I don’t make black music / I don’t make white music / I make spite music,” he summed this up perfectly. Rival musicians, homosexuals, past lovers, journalists and critics – though not Jews – have all been fair game for Slim Shady’s quick-fire bile.

Off the back of this, an argument could possibly be made that if you claim to hate everyone, perhaps you don’t actually hate anyone. You’re just a general hater. Or you’re being an entertainer living up to your bad-boy image. Brooklyn-based hip hop writer Joe Berkowitz told the Jewish Chronicle in 2011 that there is a level of permissiveness that exists in rap that doesn’t exist in other areas of music. He said it appears that rappers can get away with being “casually anti-Semitic”, particularly if it’s done in an amusing way or used as a punchline. Which begs the slightly wider question of whether rappers are just playing a role and don’t ever mean anything they say.

While the “rapper as role player” argument may wash with certain recorded songs – people listening to Eminem’s Kill You, for example, shouldn’t fear that the rapper will actually murder them if they “f-ck with him” – it’s a weak line. And it’s clearly a nonsense one when it comes to comments made in a personal capacity away from the music. No one will ever assume that Wiley was adopting a persona when he told the Jewish community that Israel was not their country. “Rapper as role player” is also, incidentally, an extremely dangerous line of defence: it’s a consequence-free charter for hate.

Some commentators have argued that people are too “woke” these days to call out hate speech by rappers lest they themselves are accused of discrimination. This is a reductive argument that, taken to its logical conclusion, means that no one would ever speak out about anything, and hate speech would be allowed to continue unabated.

Shame on the Hollywood Reporter who obviously gave my brother Kareem 30 pieces of silver to cut us down without even a phone call. https://t.co/XRXPu0NRBW

— Ice Cube (@icecube) July 15, 2020

So what can be done? Danny Stone, the chief executive of the Antisemitism Policy Trust, tells me that the focus should be on the social-media companies. “Irrespective of whether it’s hip hop or gaming,” he says, “or any other online communities, too often we are seeing anti-Semitic conspiracy theories circulating online. We are looking for the Government to bring forward the Online Harms Bill. They need to do it as soon as possible.” He says that the casual anti-Semitism in hip hop needs to be highlighted and challenged whenever it occurs.

But what about the cause? While the measures Stone outlines are about tackling anti-Semitism at the consumers’ end of the process, what about stopping the lyrics being written or the theories taking root in the first place? Can anything be done?

“To me,” he says, “it’s all about education. At the moment, how do children learn about anti-Semitism in schools? It’s through the prism of the Holocaust, which is extremely important. But actually we aren’t doing enough teaching on discrimination at school. At the moment Personal, Social, Health and Economic [PSHE] isn’t on the curriculum. That’s one of the ways we could do more to talk about discrimination with kids.”

The one positive aspect of the Wiley controversy is the almost universal condemnation he’s received. In the past, sneakily anti-Semitic quotes, lyrics or Tweets would go largely unremarked – no apologies made, no lessons learnt, careers left untouched. Wiley is yet to make an apology – but this time, his career may never recover.