Specialized domestic violence court now up and running in P.E.I.

Prince Edward Island's specialized court to deal with some domestic violence cases is now six months old, and more than a dozen offenders are taking part in the new system.

The new court started operating in January.

It's for people accused of domestic violence who enter a guilty plea and are willing to take responsibility for their actions, as well as open to taking part in programs recommended to help them change their behaviour.

"This is the first specialized court or therapeutic court in the province," said Bobbi Jo Flynn, the director of policy and planning with P.E.I.'s Department of Justice and Public Safety.

She described the new court process as a type of intense and "much more timely" intervention, a mixture of programming and a traditional criminal court with normal court procedures.

P.E.I. Victim Services stats show there were more than 1,000 cases involving family violence in 2018-2019, the most recent year for which comprehensive figures are available. Child protection investigations numbered close to 2,000 that same year.

Flynn said programs to help the offender address behavioural issues get started quickly under the new court system, and a case management team monitors the person and assesses progress.

Lawyers and judges are involved, along with caseworkers looking at what types of counselling or addictions treatment programs a person might need.

The victim of the domestic violence also has a voice in the process, through staff of the provincial Victim Services office.

Flynn said the offender guilty plea required for participation in the new court can make it easier for some victims because it means they don't have the stress of having to go through a trial and answer questions under a defence lawyer's cross-examination.

Different types of violence

Domestic violence can involve physical attacks, but it can also be mental manipulation, financial restrictions or any kind of controlling behaviour.

"We may also see people who engage in coercive behaviours, more controlling behaviours. There may have been emergency protection orders in place or stay-away orders... It might not always be physical violence," said Flynn.

Calling this a "therapeutic" court reflects that it's designed with simplified proceedings, provides more support for victims, and gets the offender to take responsibility and consent to participate in whatever interventions may be needed.

"Not everybody is going to be suitable," said Flynn. "This isn't for every person, and the obligations on the accused are significant."

'PEI one of the last to get it'

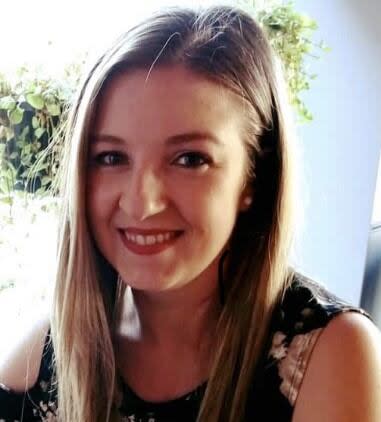

Mary Aspinall worked as a front-line victim services worker in the past, and has also done extensive research on the domestic violence court model.

She said it's good to see P.E.I. adopt it.

"I'm really glad to see this is progressing. It's one of the last provinces to have a specialized court," said Aspinall, an assistant professor in the Department of Criminology and Criminal Justice at St. Thomas University in Fredericton.

Aspinall said criminal courts were not typically dealing with the root causes and underlying issues involved in domestic violence cases.

"The development of the domestic violence court was to really take a more holistic approach," she said. "There needs to be that early intervention for offenders, that there's access to rehabilitation... as well as considering victim safety."

Aspinall said domestic violence is a "huge problem" that affects many people throughout Canada, and a court that allows for more communication and collaboration with community services and other agencies has the potential to make a difference in P.E.I.

She pointed out that going through the programming requires a high level of commitment, and it can be harder than just being sentenced in a normal court.

"This is not the easy way out," she stressed. "There is a lot of work that goes into this.

"While they are going through these interventions and treatments, they are being monitored and they are being surpervised. They are held accountable."