Why Europe's efforts to stop a second wave of Covid were doomed to fail

The sun was shining, the drinks were flowing, and there was even music in the air.

It was July 1 this year, and while the pandemic continued to rage in other parts of the world, the Czech Republic was hosting a 'farewell party' for Covid-19, held on Prague's iconic Charles Bridge.

“This is a celebration to show people that we are not afraid and we do not have to remain locked in our rooms,” the organiser, Ondrej Kozba, boasted, as the country emerged from a strict, quickly enforced lockdown, relatively unscathed by its initial brush with the deadly virus.

Four months later, the Czech Republic has one of the fastest growing epidemics in the world, with almost 300,000 cases and 2,675 deaths, three-quarters of which were reported in the last month.

But the country is not alone. In the last even days Europe reported some 1.5 million cases, nearly half of all new infections worldwide, and surpassed the grim milestone of 10 million cumulative cases. Deaths have also risen by 32 per cent, to 11,733, and now account for nearly one third of all new fatalities globally.

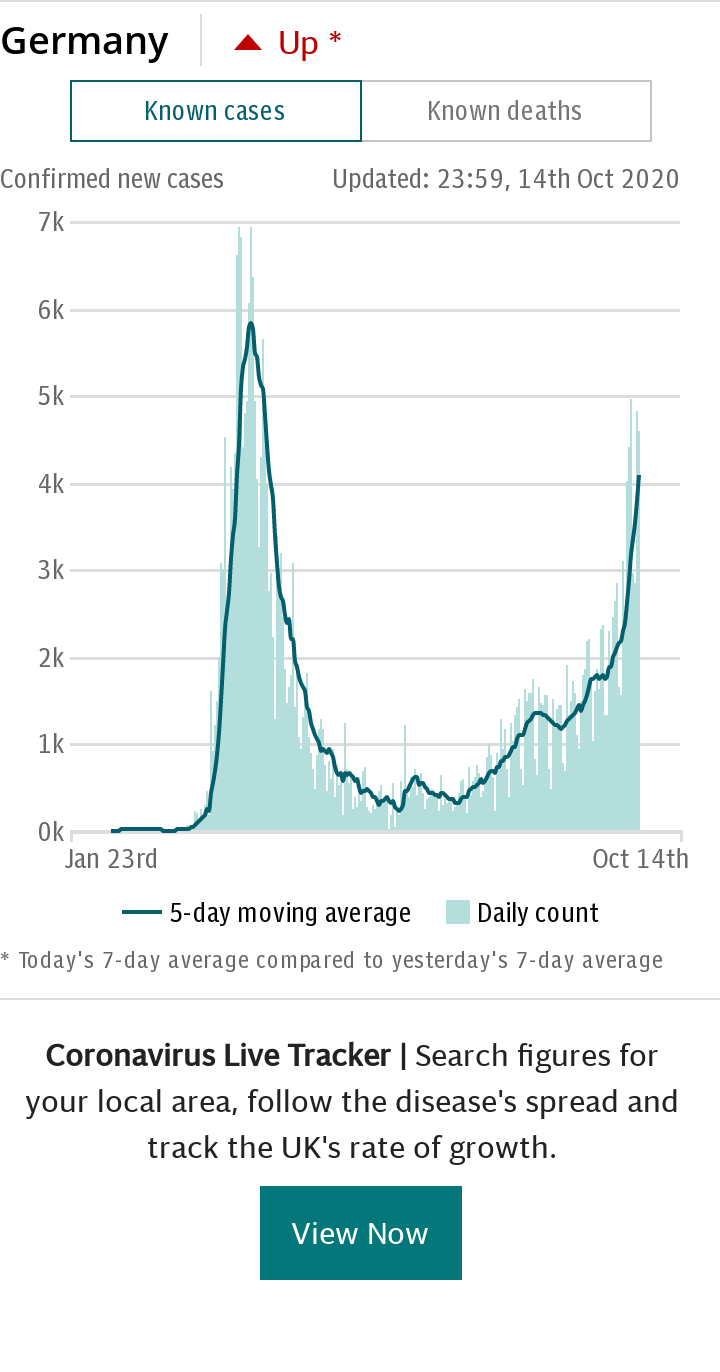

The last fortnight has seen a number of countries, including Germany, France and the Czech Republic, tighten restrictions in an effort to curb spiralling infection rates. But how did things get so bad - again? After all the warnings, how is Europe on the verge of being brought to its knees once more by coronavirus?

Many of the problems originate in the summer, when countries rushed to reopen without first building sufficient capacity in the public health scaffold, says Martin McKee, European public health professor at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine.

“In a number of places the problem was they opened up before the epidemic was really under control in the first place. Contact tracing systems were just not up to it.”

From that point onwards, many never had a chance as cases only went one way: upwards.

For instance, Spain exited its three month lockdown in June, yet by mid-July had hired just 3,500 contact tracers. That figure has since risen to around 8,500, including specially trained members of the armed forces, yet compliance is low - just 55 per cent people quarantine after coming into contact with a Covid positive individual.

“We didn’t do our homework,” says Daniel López-Acuña, an epidemiologist advising the Spanish region of Asturias. “Several regions failed to strengthen primary healthcare, do enough PCR testing and boost tracing services until the second wave was already here.”

Health workers have added that test results are too slow to be effective, while the positivity rate has soared to above 10 per cent. The World Health Organization says anything over 5 per cent is “too high”.

Meanwhile in Belgium, authorities have moved to exclude those who have returned from a high risk area abroad or been in close contact with an infected person, as laboratories were overwhelmed.

And in Italy, just 1,775 Covid-19 positive people are using the aggressively marketed App Immuni - a tiny fraction of the 20,000 confirmed daily cases - while people have waited up to 11 hours in queues at drive-in testing centres.

The situation barely improves in neighbouring France, where President Emmanuel Macron has conceded that the struggling test and trace system needs to be “redeployed” as he announced a stringent second lockdown.

While the country had massively ramped up capacity after a slow start, testing 1.9 million people last week, infectologist Xavier Lescure has warned that contact tracers have “clearly been overwhelmed for some time”. Just 48 per cent of people receive results within 24 hours - a figure dropping by the day.

Even Germany, where highly efficient systems in March and April were credited with keeping fatalities low, appears overwhelmed by sheer numbers. On Friday alone there were 18,000 new cases, meaning close to 100,000 contact people who need to be told to self-isolate - the army has now been called in to help.

Experts, including the country's top virologist Christian Drosten, have called for a change of strategy: ignore the people who a person could have infected and concentrate on “clusters” - events when lots of people were infected at once.

Yet, when announcing new lockdown measures on Wednesday, Merkel said that health authorities could now only identify where 25 percent of cases came from - and most of these were inside families. Meanwhile the Corona-Warn-App has registered just two per cent of known cases.

With hindsight, experts say the collapse of the continents test and trace capacity was almost inevitable.

“In the summer we did the hard work to get numbers low,” says Devi Sridhar, professor of global public health at Edinburgh University. “But the question is: should we have driven numbers lower, held lockdown for a few more weeks, really reinforced our test and trace system and put in checks in place to prevent importation?”

There is good reason, she adds, why South Korea, Taiwan and China, where the virus originated - have not experienced a second wave of anything like this severity, despite seeing multiple outbreaks.

The continent, unlike Asia, never truly got hold of its pandemic before bursting out of lockdowns into a summer holiday season charged with pent up demand for quintessentially European phenomenon of vacations abroad.

“What we are seeing in Europe in general is that everyone went on holiday in August, and people took Covid to countries like Greece, which was actively trying to attract tourists, and which had been relatively unscathed,” says Prof McKee. Then they brought it back to the countries they came from. That's the simplest explanation.”

His theory is backed up by a study this week from the University of Basel, which found that a new genetic strain of coronavirus, first seen in Spanish farm workers, is now responsible for the majority of infections in Europe, including 80 per cent in the UK.

But the continent was also lulled into a false sense of security. Upticks in cases at the end of summer were dominated by young people and, because they are less vulnerable to serious complications from Covid-19 and so deaths remained low - at first.

“Nobody listened to those of us warning about this,” says Prof McKee - now the modelling for the rest of the winter in Europe now looks “frightening”.

“We missed our opportunity,” adds Prof Sridhar. “In Europe it feels like we're competing to not be the worst.”

Protect yourself and your family by learning more about Global Health Security