It won’t be easy for Boris Johnson to keep his pledges to his new friends in the north

Until election night, I very much doubt that the typical Tory member in the home counties, or the average Conservative MP from the southern shires, could have found Blyth Valley on a map. The best they might have managed is that it lay up north in that mysterious and unknown area of the country that they had mentally marked: “Here Be Dragons”. Now a Conservative MP sits for the Northumbrian constituency, which has never previously been represented by the Tories. Ian Levy’s victory was perhaps the most sensational, and certainly among the most symbolic, of the dramatic gains that the Conservatives made at the expense of Labour.

The December election sent more than 100 new Tory MPs to parliament. It is a striking fact that they of Conservative MPs account for half of the backbenchers sitting behind Boris Johnson. His new friends from the north speak in different accents to their more southerly colleagues. They often think differently as well. And they represent areas of the country with needs and concerns that have been alien to the Tory party over many decades. Neil O’Brien, the Conservative MP for Harborough, points out that Tories represented just 14 seats in the most deprived half of England in 2001. Now Conservative MPs sit for 116 of them. This could give them a lot of clout if they get organised. There are signs that they are. More than 120 Tory MPs have signed up to the Blue Collar Conservatism caucus that will have its first meeting tomorrow evening.

Mr Johnson says that he understands these seats are only “on loan” to the Tories. Also correctly, he has observed that the Conservative party will have to change if it is to convince those who voted for it for the first time that they made the right decision. To use the sort of metaphor he will readily understand, his relationship with these new Tory voters is not necessarily for the long term. Many of them jumped into bed with him on 12 December because they wanted Brexit and loathed Jeremy Corbyn, not from any great love of either the Tory leader or his party. Mr Corbyn will definitely not be a factor at the next election; Brexit may or may not be a factor depending on what it does to the economy. Our Opinium poll today finds the public evenly split on whether the Conservatives will deliver for voters in the seats that they took from Labour.

Talking to allies of the prime minister, I find that they privately acknowledge that one of their stiffest challenges is delivering palpable progress in the “left behind” areas of the country that they now represent. I also often hear a ready acceptance that they are far from being at the point where they can say confidently that they have worked out how to do it. The suggestion that Conservative campaign headquarters might be relocated somewhere north is a wheeze designed more to serve the interests of the Tory party than anyone else. The occasional cabinet meeting convened outside London (not a new stunt; David Cameron did that as well) isn’t going to solve deep-rooted, multigenerational problems. Talk of “levelling up” the north, the rhetorical trope that has become highly fashionable among ministers since the election, is no more than blather until we see the colour of the money. It is not a bad idea to recast the Treasury’s rules to help regional projects to secure more approvals, but it will only be a winning formula if productive ideas result. Beaten-up high streets will not be reinvigorated easily or overnight. Higher skills and better employment opportunities cannot be magicked up with a wave of Whitehall’s wand.

There has been much conjecture that we are going to see a fresh kind of Toryism, a version less laissez-faire and more activist. Last summer, Tory ministers behaved exactly as we would expect Tory ministers to act when they allowed Thomas Cook to go bust on the grounds that it is not the role of government to salvage failing holiday companies. In an inversion of that doctrine, ministers have just intervened to prop up the ailing airline Flybe, much to the consternation of its competitors, which are crying foul and threatening legal action. The reason ministers did so is because Flybe operates a selection of often unprofitable routes that connect regional airports. Is this an early hint that the Johnson government will be a lot more interventionist? It is much too premature to be sure of that. This may just be a sign that he did not want to aggravate some of his new Tory voters and his new MPs so soon after they put him back in Number 10.

What is instructive is the grumbling response of Thatcherite Tories, complaining on the evidence of this one intervention that Conservative economic policy is already turning too pink for their liking. There is a substantial wing of the Tory party, a faction that has heavy representation around the cabinet table, which remains viscerally hostile to an active state. A manifestation of that is the ongoing battle within government over the high-speed rail link. There is fierce lobbying to scrap or downgrade the project, even though billions have been spent and construction is under way. Andy Street, the Tory mayor of the West Midlands, and other regional civic leaders will respond to cancellation with fury. This will be an early test of Mr Johnson that colleagues believe he cannot afford to fail. “Boris sold himself as Mr Infrastructure during the election,” says a senior Tory. “Will he really want one of his first big acts since he was returned to Number 10 to be axing the biggest infrastructure project ever?”

The Tory election prospectus committed to spending £100bn on infrastructure and Sajid Javid’s budget in March will feature many plans to improve the physical fabric in the regions. The big-ticket items will take years to complete. Tory political hopes are more invested in smaller, shovel-ready projects designed to produce dividends before the next election. The government is putting a lot of faith in the power of infrastructure spending to boost economic activity in the Midlands and the north. This is not necessarily because it will always be the best thing to do, but because commissioning construction projects is something that government thinks it knows how to do. It is also because we have a prime minister who, since his days as mayor of London, has never seen a bridge proposal that he did not like. Infrastructure spending can bring benefits, but we should be wary of the idea that it is a problem-killing silver bullet. Putting money into better roads and faster rail services can be more harmful than helpful to struggling towns if it serves only to syphon off more commerce, talent and prosperity to cities.

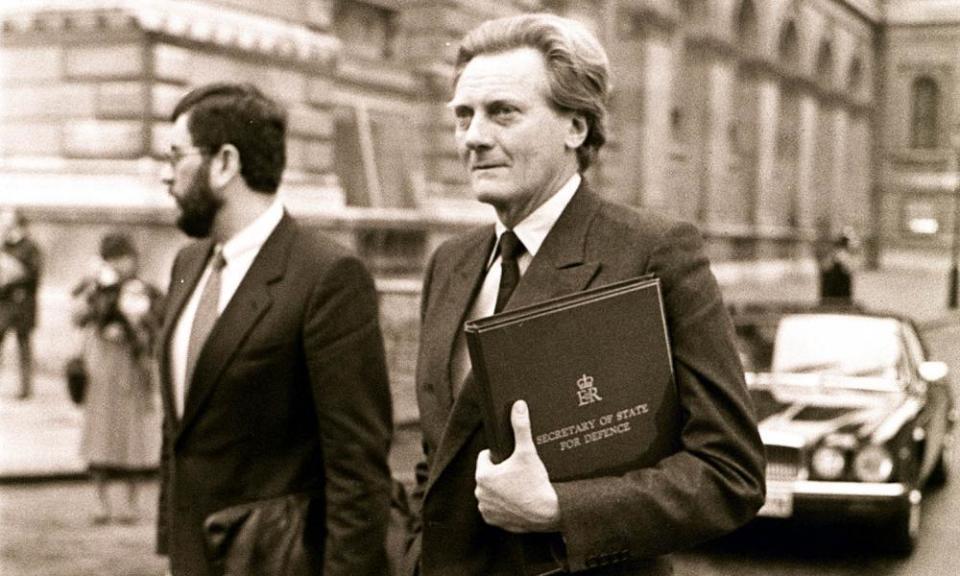

Mr Johnson is a self-styled “Brexity Hezza”. If he listens to the man who pioneered Tory ideas about urban regeneration in the 1980s, he will take Michael Heseltine’s advice to give communities much more control over their destinies and capability to attract high-value industries providing good quality jobs. The devolution of powers will be meaningless without the resources to do anything with them. A Tory cabinet serious about doing something for the less affluent regions will have to start reversing the protracted and severe squeeze on local government budgets. “There’s got to be a very visible end to austerity,” said one of the senior Tories I talked to about this challenge. “There’s also got to be tangible improvement in the external reality of the ‘left behind’ places so there’s some sense that they are catching up with London and the south-east.”

This has significant implications for the shape of public spending. The Tories have pledged to increase resources, especially for schools, the health service and policing. Rachel Wolf, co-author of the Tory manifesto, sets one test for this government: “In five years, people need to find it easier to get a GP appointment, think A&E and social care is better, not worse, and not believe that their schools are struggling with budgets.” Precisely where all the money is going to come from is moot when Mr Johnson pledged not to increase any of the main forms of personal taxation.

Delivering for his new voters and MPs will mean not just ending austerity but skewing future spending and investment more in favour of the less affluent areas of the country at the expense of the traditional blue heartlands. Despite the changes in the complexion of parliament wreaked by the election, the majority of Conservative MPs still sit for southern seats. We will know that this is truly a different kind of Tory government only when its shire MPs are heard to complain that Mr Johnson is doing too much for Blyth Valley.

• Andrew Rawnsley is Chief Political Commentator of the Observer